Who Let These Men Say 'Dyke'?

The merits of revisiting "Go Fish," "Chasing Amy" and "Dykes to Watch Out For."

One of my recent Etsy sales (to a lovely friend who works at Outfest, perfectly) was John Pierson’s Spike, Mike, Slackers and Dykes: A Guided Tour across a Decade of American Independent Cinema.

Who gave this straight cis white dude permission to say dyke? If I say “Guinevere Turner,” that might not be a surprise.

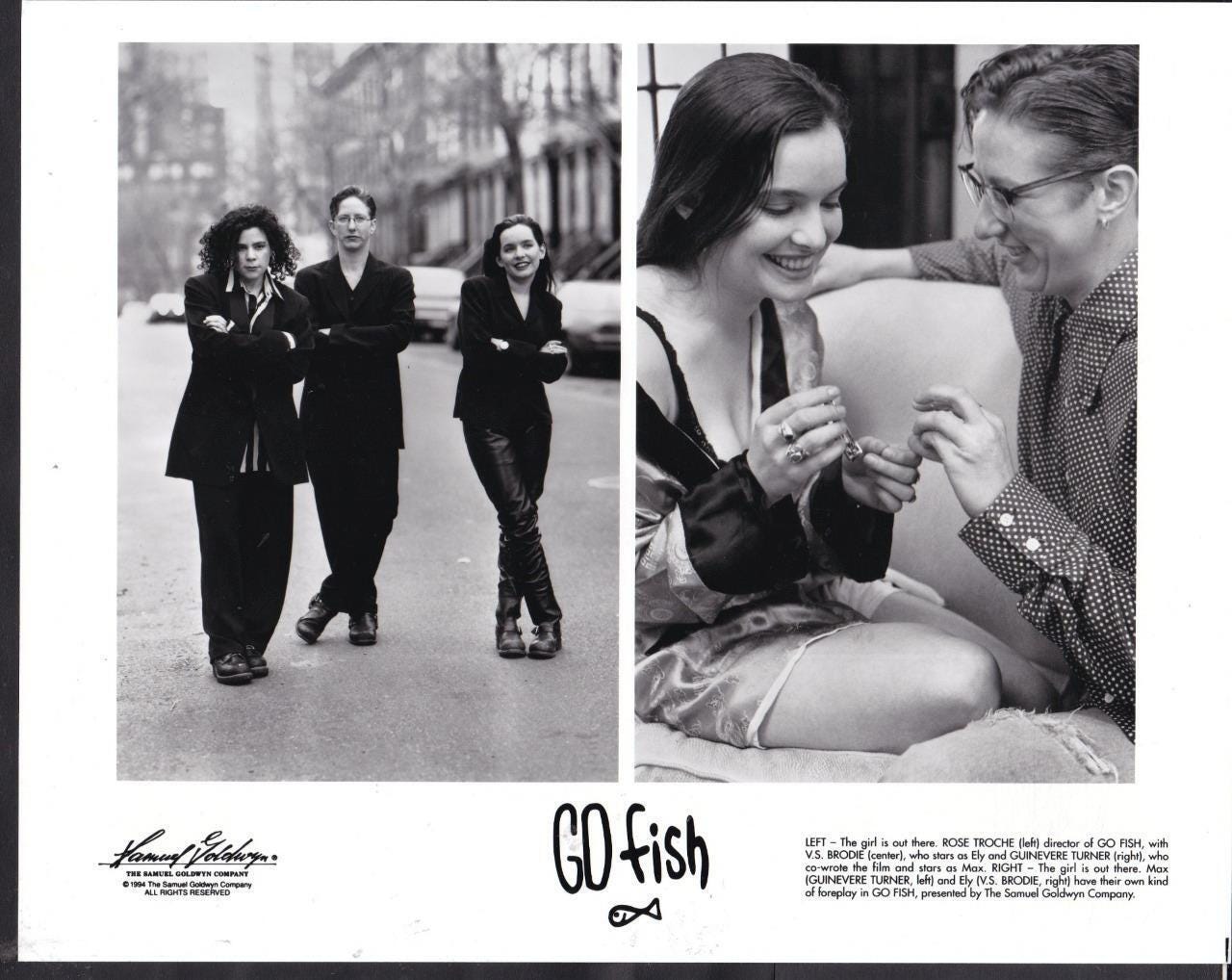

John Pierson was instrumental in the success of She’s Gotta Have It (the Spike), Michael Moore’s first doc Roger and Me (the Mike), Kevin Smith’s Clerks (said slackers), and Turner’s big screen debut Go Fish (the dykes) in the 1990s. In his book (published 1998), he detailed his experience of meeting Guinevere Turner and Rose Troche, already ex-girlfriends but still collaborators on the DIY black-and-white lesbian film they were already half-done with. They had free labor from their Chicago dyke community but no money to finish the film. Troche credits B. Ruby Rich’s “New Queer Cinema” with having inspired them to make a movie at all, but it was Christine Vachon’s producing work on Poison and encouragement for queer filmmakers to keep making work that led to a passionate letter to Vachon, who connected them with John Pierson. Pierson’s guidance and funding were crucial to the historic Sundance sale that took place when Samuel Goldwyn plucked Go Fish from the tank just in time for the movie to hit theaters that June for Pride.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Go Fish lately, not only because of the great behind-the-scenes information available in Pierson’s book (Vachon has her book, Shooting to Kill, where she points to Pierson’s for more specifics), but because I was lucky enough to have a small role in a new documentary that just premiered to wonderful reviews at Tribeca and will be playing film festivals like Outfest’s Closing Night the rest of the summer: Sav Rodgers’ Chasing Chasing Amy.

Kevin Smith’s Clerks follow-up Chasing Amy and Go Fish are inextricably linked, stemming from that fateful Sundance 1994 where Guinevere Turner struck up a “romantic friendship” with Clerks producer Scott Mosier and inevitably inspired Smith’s 1997 rom-com about a lesbian who has an identity crisis when she falls for a cis man.

The merits of a film following a lesbian falling for a cis straight guy have been long debated, and I’ll let Chasing Chasing Amy handle the nuances of a film that can be read as a trans-masc narrative in addition to a queer or bisexual one. (For a great in-depth history of Chasing Amy, read Shannon Keating’s 2017 20th anniversary reflection featuring both Turner and Smith.) Instead, I’m interested in the relationship Chasing Amy and Go Fish had in propelling lesbian film forward, and their place in queer history. I find them to be in conversation with each other, especially around the idea of dyke humor (what’s funny to dykes vs. non-dykes) and their mutual focus on identity as it relates to who is fucking who (very of its time, but also still relevant.) Both typed romantic comedies, Go Fish’s tagline was “The girl is out there,” while Chasing Amy’s: “It's not who you love. It's how.”

Lisa Henderson once wrote that the Go Fish ensemble was like a live version of Dykes to Watch Out For, and with its fashion, ephemera and dialogues, both are highly valuable assets from a time when all of these things were crucial to a collective lesbian identity, which was also allegedly diverse and anti-monolithic. Without an actual queer woman like the literal writer and star of Go Fish, the comedy of Chasing Amy would have fallen flat — but instead, the convergence of New Queer Cinema, lesbian chic and indie bro comedy is now home to on-screen depictions of historical artifacts and locations like Meow Mix, a pivotal and beloved NYC sapphic space from 1996-2004. It’s at Meow Mix where Alyssa (Joey Lauren Adams) sings to her girlfriend, backed by women on guitars, and leaves the stage only to kiss her partner passionately mid-song.

Of course, the humor of the scene is intended for audiences who, just like Ben Affleck and Jason Lee, might finally realize they’re in a lesbian bar. The rest of us (raises hand) were probably hoping to stay inside forever.

Chasing Amy will never pass The Bechdel Test, but it was, itself, a byproduct of Alison Bechdel’s iconic comic strip which should have moved to the big or small screen. Instead, 40 years after its debut in weekly gay newspapers, it found enough support (from Susie Bright, thank goddess) to get its own Audible audiobook. Narrated by Jane Lynch, famous queer women Roxane Gay, Roberta Colindrez and Carrie Brownstein all leant their voices to the iconic characters like Mo, Lois, Toni, and Clarice “as they surf the waves of dyke drama from the softball field to the women’s bookstore, from the brunch rush at the vegan Café Topaz all the way to the steps of the Supreme Court, in a very special episode set at the landmark 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.” The lesbian nostalgia is aided by the soundtrack of Ferron, Holly Near, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Cris Williamson, and Joan Jett.

Though she continued with the characters until 2008, Bechdel said she found the post-lesbian chic era of Y2k to be less than friendly to lesbian content. She told Vulture:

“The whole gay scene was disintegrating by the early 2000s. It started to get harder for me to earn a living from my comic strip. The internet was replacing newspapers; gay and women’s bookstores were closing. My publisher had gone bankrupt. I was on this iceberg that was starting to melt. I had an agent who was trying to sell my next Dykes collection to a mainstream press, and no one was interested. They were saying, ‘People don’t need this work the way they once did.”

The relative success of Go Fish, Chasing Amy,The Watermelon Woman (in which Turner also plays a significant role), Nicole Conn’s Claire of the Moon, the Wachowski Sisters’ Bound (which deserves its own retrospective from a trans-femme perspective, IMHO) and The L Word (first greenlit as “Earthlings” by Showtime in 2002) were part of a changing tide in lesbian cinema and TV, but also gave the false impression of an oversaturated market for what was still considered a niche audience. And with Chasing Amy having done “better” at the box office than Go Fish ($12 million vs. $2 million), male viewers (and sometimes aueters) with their voyeuristic POVs were still highly prioritized.

In that same 2021 interview with Vulture, Bechdel said she’d written a television pilot and wanted to create “an animated series based on my drawings,” updated for the present but still set in the ‘90s. Though an audiobook voiced by celesbians is not exactly what she may have had in mind, the sentiment she shared around the continued relevance of DTWOF having taken place in a specific place and time for dykes rings true:

“For older people, it might be nostalgic; for younger people, they’re curious about what now was a long time ago. When I was a teenager, I would watch movies that were 30 years old, and they seemed prehistoric.”

Chasing Amy and Go Fish may feel pre-historic to Gens X and Z, but revisiting them is part of the constant evolution and context we have for queer films and queer history. Salvaging and reclamation are essential to our individual and collective futures, something Guinevere Turner does in her new memoir about her youth spent in the Lyman Family cult, and both Turner and Kevin Smith do for their respective roles in Chasing Chasing Amy. (Not for nothing, Guinevere Turner was a writer and guest star on the original L Word — one of few cast members who were out at the time — while Joey Lauren Adams was cast as Alice’s love interest on the final season of Generation Q, a direct nod to her role in our herstory. These connections continue…)

I haven’t seen Chasing Chasing Amy yet, but I’m feeling grateful to have been a part of a project that continues to build on our shared history and expands the queer canon to include the trans perspectives that haven’t been considered. I rewatched Chasing Amy before I did the interview a few years back, and enjoyed the opportunity to find what was different for me now — what I’d discover (new? old?) to reconsider like I do each time I revisit Go Fish. Hopefully, it will be in a theater full of dykes and queers for its 30th anniversary next summer.