The Black Queer Literary Queen of Martha's Vineyard

Dorothy West was best known as the last surviving member of the Harlem Renaissance yet her legacy remains under-acknowledged.

My sister was visiting recently and, an admitted Bravoholic, was catching up on her shows when I heard someone on screen say, “So, our next house is the house of Dorothy West.”

The cast of Summer House: Martha’s Vineyard was taking a tour of the African American Heritage Trail, and the last stop was Dorothy West’s Oak Bluffs cottage. The late writer’s historic home resides on Dorothy West Avenue, named in her honor after a brief career revial at the end of her life almost 20 years ago.

“Now most of you guys probably heard about The Wedding?” the tour guide asks the group, eliciting several confused “no”s.

“The book The Wedding?” she tries again. “Or the movie with Halle Barry in it?”

One of them has heard of the movie, she thinks, but not one of them is familiar with Dorothy West.

Unfortunately, cameras did not take us inside the historic home where West lived and worked from the 1940s until her death in 1998, just a few months after The Wedding aired on as a two-part mini-series ABC. West’s mention on Bravo was brief, utilized to show how little the Summer House cast (young, Black and upwardly mobile) knows of their history, specifically as it applies to a particularly historic neighborhood on the island. Not that they are to blame when a racist and sexist educational system frequently excludes Black writers, queer writers and women writers and leaves little room for someone like West, who was all three in one.

West’s work spanned decades — her contemporaries were the likes of Zora Neale Hurston (with whom she tied for first place in a shorty story contest early in their careers) and Langston Hughes. She penned stories, newspaper columns and two novels — her first, The Living is Easy, published in 1948, almost 50 years before The Wedding would follow. The Living is Easy fell out of print but was picked up in 1982 by Feminist Press, giving West a career renaissance she’d only dreamt of during a lengthy period of rejection and erasure.

It was Feminist Press that brought West back into the limelight, providing her the public and private support to finish her second novel while her star rose with her travels to speak at colleges and universities as the last living member of the Harlem Renaissance. The renewed fervor in West’s work led to Doubleday publishing The Wedding. Set in Martha’s Vineyard, 1953, following an upper-class Black family not unlike West’s own, the plot revolves around a light-skinned Black woman, Shelby, on the days leading up to her wedding to a poor white jazz musician named Meade. Issues of race, class and caste threaten Shelby and Meade’s big day, with family secrets and prejudices coming to the fore.

Oprah Winfrey was so taken with West’s novel that it was her Harpo Productions that transformed it for TV, debuting during Black History Month. The script was adapted by Lisa Jones, co-writer of three books with Spike Lee as well as her own memoir and Bulletproof Diva, a collection of her work for the Village Voice. Despite their best efforts, The Wedding received poor reviews, finding it melodramtic and poorly cast, and faded into relative obscurity, which is why it’s not so strange that a new generation might not recognize “Dorothy West.”

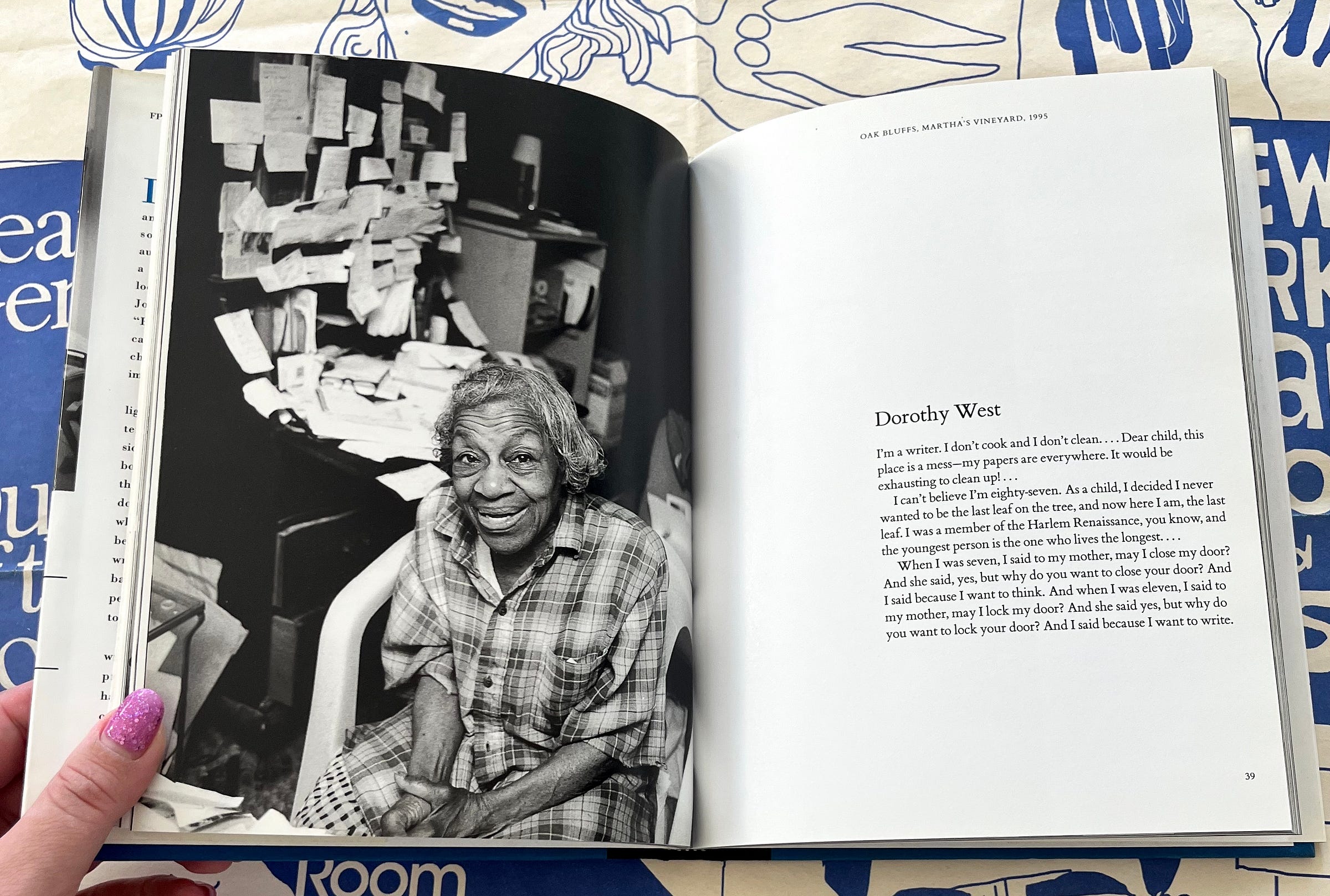

Salem Mekuria’s documentary As I Remember It: A Portrait of Dorothy West (1991) is one of the best ways to get acquainted with West and her world in the years after her Feminist Press re-issue. In the doc, West talks about her decision to never marry or to have children, preferring life with her work, her three cats and the countless visitors who appeared in profiles and interviews conducted at the end of her life, when The Wedding had brought her back into public consciousness. (It didn’t hurt that the book was dedicated to her friend and neighbor, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who encouraged her to finish writing it despite West’s concerns that radical civil rights groups would find its themes on class and interracial marriage in poor taste.)

The Wedding is both literally about racial prejudice but can also be read as an allegory for familial homophobia. West, like many of the creatives of the Harlem Renaissance, was queer though seldom discussed in her writing or interviews. She’d had a relationship with Marian Minus, an intellectual who worked at West’s lefty literary magazine The Challenge, eventually co-running the publication together. Minus was herself a gifted writer whose stories “Girl, Colored” and “The Fine Line” remain important texts of the Black Chicago Renaissance, yet she doesn’t even have her own Wikipedia page. She is made brief mention of in a few books about the South Side writer’s group she was part of, but it’s her correspondence with West (as found in West’s archives) and the articles she wrote for places like Woman’s Day (and how I love that there was a Black lesbian Marxist at Woman’s Day!) that offer glimpses of Minus, who her bisexual contemporary Margaret Walker once described her as having "dressed mannishly and looked lesbian in male fashion."

Both West and Minus attempted to rectify the misogyny of editor Richard Wright at The Challenge, as well as the more generally sexist attitudes of their era. (Minus penned a positive review of Their Eyes Were Watching God after Wright panned Zora Neale Hurston’s iconic book in print. It was a real sisterhood.) Together, West and Minus published and championed work by women writers like Margaret Walker, Mae Cowdery, and Pauli Murray.

In Dr. Verner D. Mitchell and Cynthia Davis’s introduction to a collection of West’s writings, Where the Wild Grapes Grow, it’s documented that West aligned herself with women writers “for various reasons,” also naming Edna Lewis Thomas, Blanche Colton Williams, Dorothy Scarborough, Mildred Jones … each of whom made a unique contribution to her life and work." Still, they note, West kept her queerness under wraps best she could manage.

“Like her friend Alberta Hunter, the blues singer, who maintained a discreet lesbian lifestyle and never admitted she was gay, West had grown up in a household that frowned on all discussion of sexuality, let alone homosexuality; probably neither woman had the language with which to describe her orientation. For years West and Hunter socialized with the same coterie of gay men in New York, including Ed Perry, Caska Bonds, Bruce Nugent, and Alex Gumby, and gave similarly evasive answers when asked why they never married. As Margaret Walker points out, at that time “polite society ostracized the individual known as ‘queer,’” adding, “There was no such thing as a sexual revolution or gay rights or ‘coming out of the closet.’” In addition to fearing public censure, West always resisted labels. As she told one interviewer, “You can’t make a good Communist out of me. But then again you can’t make a good anything out of me” (Dalsgård 38). Although West never wrote about homosexuality, the many unhappy couples in her work, who sacrifice love for marriages of convenience based on socially sanctioned attributes such as color and class, reflect a dynamic that West would certainly have understood in terms of the risks of “coming out” to family and friends."

In Literary Sisters: Dorothy West and Her Circle, A Biography of the Harlem Renaissance, Davis and Mitchell surmise that Minus, an extremely intelligent and accomplished magna cum laude grad of of Fisk University, met West through mutual friends while vacationing in New York during the summer. The relationship was both romantic and work-related, as outside of their own writing, Minus typed West’s manuscripts for her and together, they mined each other’s stories and families for content. (Marian's grandmother, Laura Lyles, was the model for the matriarch, Gram, in The Wedding, as well as the young protagonist in Minus’s “The Fine Line.”)

West and Minus also pioneered a view of Black literature that, citing Gertrude Stein, combined “universality of appeal” with “the immortalization of character and social situation.” They aimed to widen the breadth of what Black writers were allowed to publish, wanting to move beyond narratives based solely on oppression. But it’s truly incredible that these two writers of the Black Chicago Renaissance, as Donyel Hobbs Williams writes of Minus, "in addition to issues of race and predjudice ... also directs attention to gender concerns and women empowerment.” Both West and Minus deserve more credit for their efforts, but, as Black queer women with challenging ideas, they’re frequently forgotten in conversations about feminist literary ancestry.

In letters, Minus affectionally addressed Dorothy as "Dot" and once wrote her, in 1936, that she is "like someone with a precious touch who knows the value of its light and shields its flame from the shifting and shiftless winds." Their conversations were about the writing life, the people they shared in common, and the book they were working on together, Jude, never published. The two lived together in New York for a time, but when finances became strained, West joined her family at Martha’s Vineyard where Minus often visited and as the Paris Review noted, “a capable mechanic, was often seen under the hood of a car while West passed her a wrench.”

Though their romantic relationship eventually came to an end, the women remained amicable, as far as historians can tell. Minus died in 1973, but West was far from alone. She had extended family and frequent visitor — so many that ater her renewed success in the ‘80s and ‘90s, she had to put up a sign on her cottage door: “Writer at work. Please call again. Trying to Make a Living.” Still, she had Oprah on speed dial and Hillary Clinton at her 90th birthday. Her goddaughter told the New York Times in 2008:

“Dorothy was like a grandmother to me and a mother to my mother. When I was 2, I started to dress myself, with everything on backwards or inside out, and say, ‘I’m going to Dottie’s house.’ Later we would talk about everything and take walks. She loved feeding the birds. She collected stray cats. I would practice my writing and reading with her. But the richness of her house should also come from other people seeing its richness. And seeing where that magnificent writing came from.”

Dorothy West may be gone but her spirit remains, handed down through generations of those touched by her work, whether they’re aware to give her credit or not. Still, an opportunity to think and celebrate her is one I’ll happily accept. Bravo, Bravo.