On My Pauline Oliveros Shit

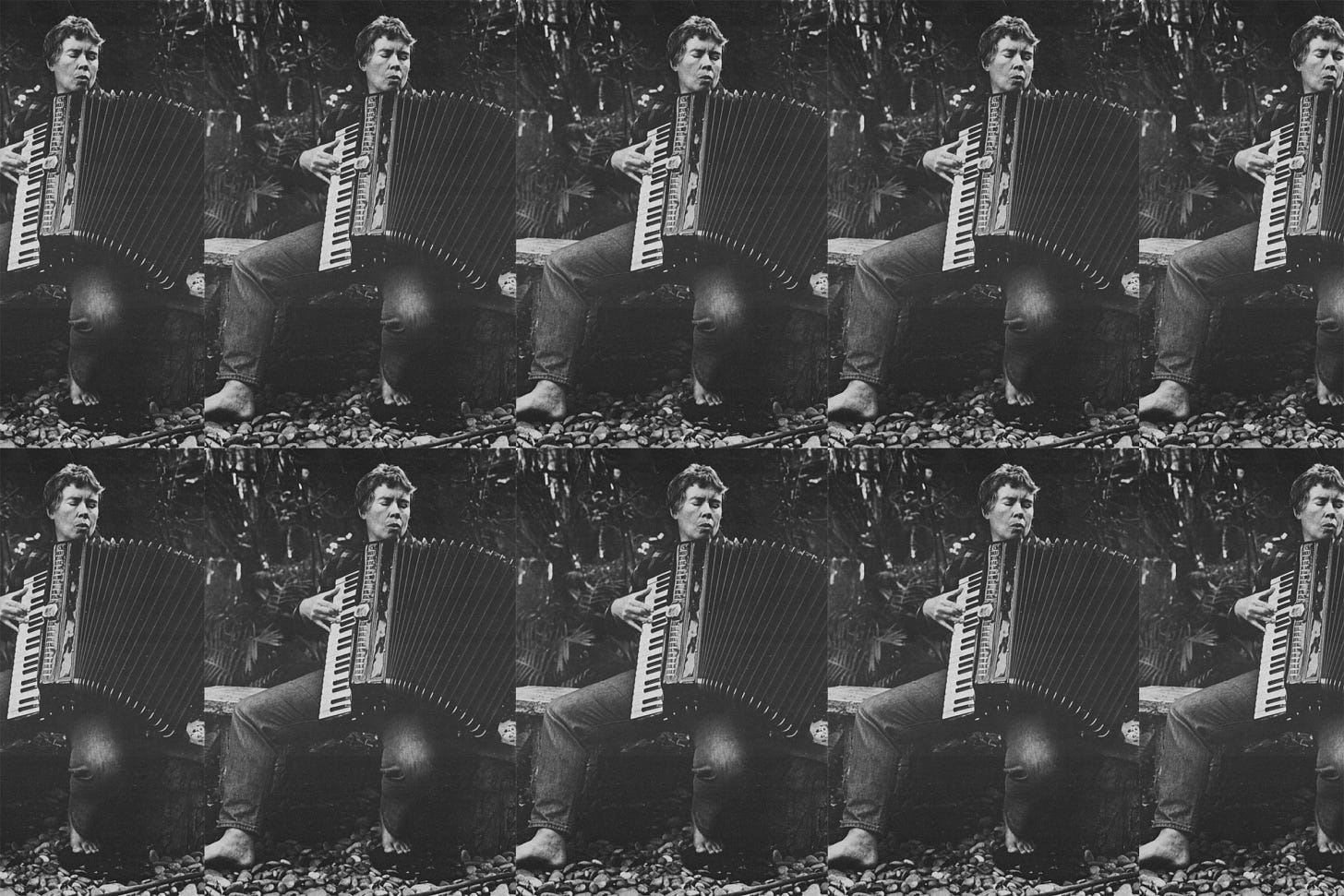

Deep Listening with the Mexican-American butch dyke who taught John Cage about harmony.

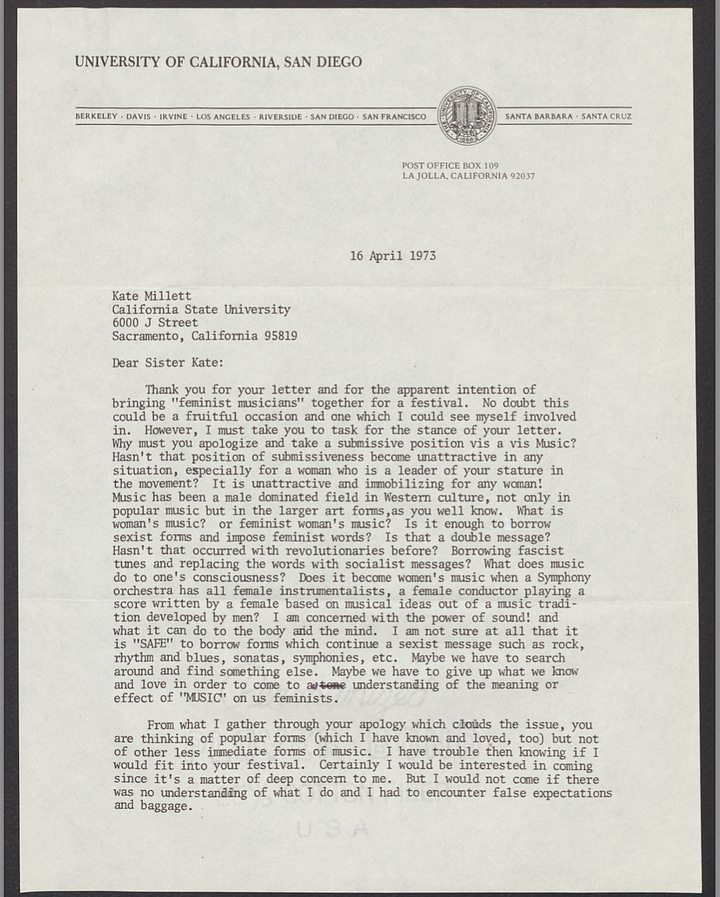

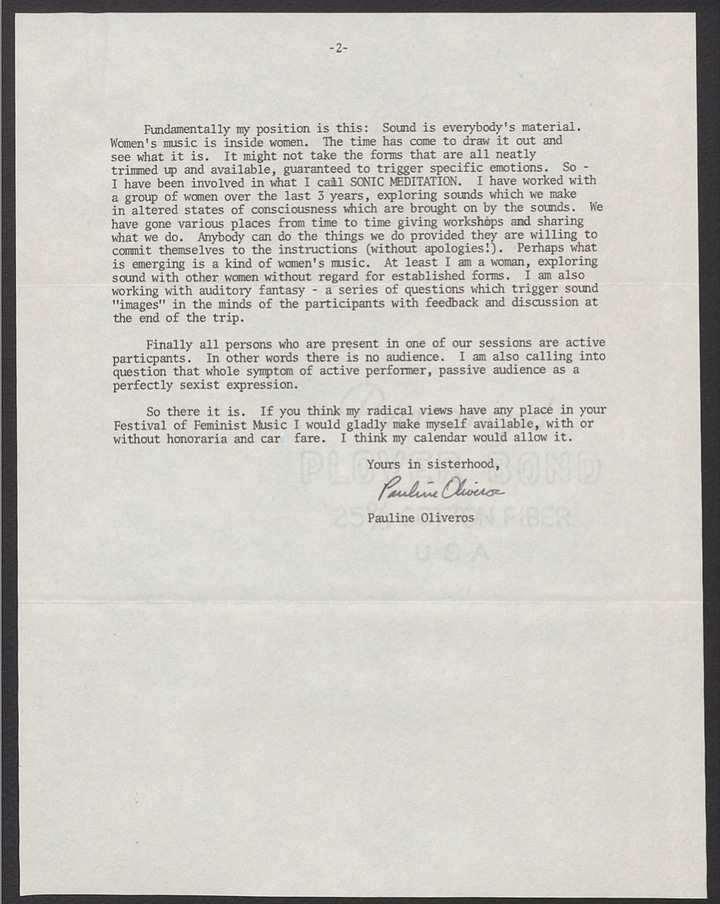

Two years ago, while digging through Kate Millett’s archive at Duke, I found a letter she’d received from Pauline Oliveros.

The letter responded to Kate’s call for women musicians to attend and participate in her first-ever women’s music festival. Pauline, by then an established electronic music pioneer and composer, had a much different take than most others who were thrilled by the opportunity and hopeful to make it work on such short funds and notice. She was enthusiastic but took Kate to task for her “apology” of a letter, in which Kate, feminist figurehead, had begun her request with an admission (“Dear Sisters in the arts who are musicians, a letter from a monotone who loves music the way any handicapped person loves the very thing they cannot do”) and ended by referring to it as a “struggle full of grace notes.”

Needless to say, I was enamored by this woman and put her in my back pocket as I continued my research into more popular forms of music, which, if you read the letter above, is antithetical to Pauline’s whole thing. But I wanted to return to her for her whole thing, and I have. I’ve been on my Pauline Oliveros shit for the last few weeks.

I took a solo trip to Ojai last week to see the new documentary Deep Listening: The Story of Pauline Oliveros. Being alone in a place where I had always been with partners allowed me to listen the way Pauline advocated: finding a balance between the internal and the external, taking in how sound moves in space, and how we either match the tones surrounding us or work hard (sometimes subconsciously) to drown them out. Initially intended for musicians to move beyond skill and perfection and fully inhabit the music within a specific space and its players, Pauline’s intent was for anyone with a body to be able to participate. As someone who has often tried traditional meditation, I find Pauline’s method of embracing sounds much more effective for me than my previous attempts to shut them out—and if this seems like a conceit for listening to oneself on a grander scale, it is.

I’ve also been practicing at home. I recently moved down the hill from the Self-Realization Fellowship, which feels like a real gift. Mt. Washington is generally a magical place—quiet yet full of things to take in. Visiting Ojai was an extension of that—a spiritually enriched town where Pauline spent time at the annual music festival, which was a perfect way to lead into the Deep Listening workshop I attended at the Philosophical Research Society over the weekend. It all felt like fortuitous timing, as I’d attended one of several Oliveros-themed performances by the Long Beach Opera last month. I’ve been reading her Sonic Meditations and listening to her works while diving deeply into her biography and methodology. (My favorite is “To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation.”) Martha Mockus’s Sounding Out: Pauline Oliveros and Lesbian Musicology and Michael Ned Holte’s Good Listener are both recent reflections on Pauline’s lifetime of work (sadly, she passed away in 2016).

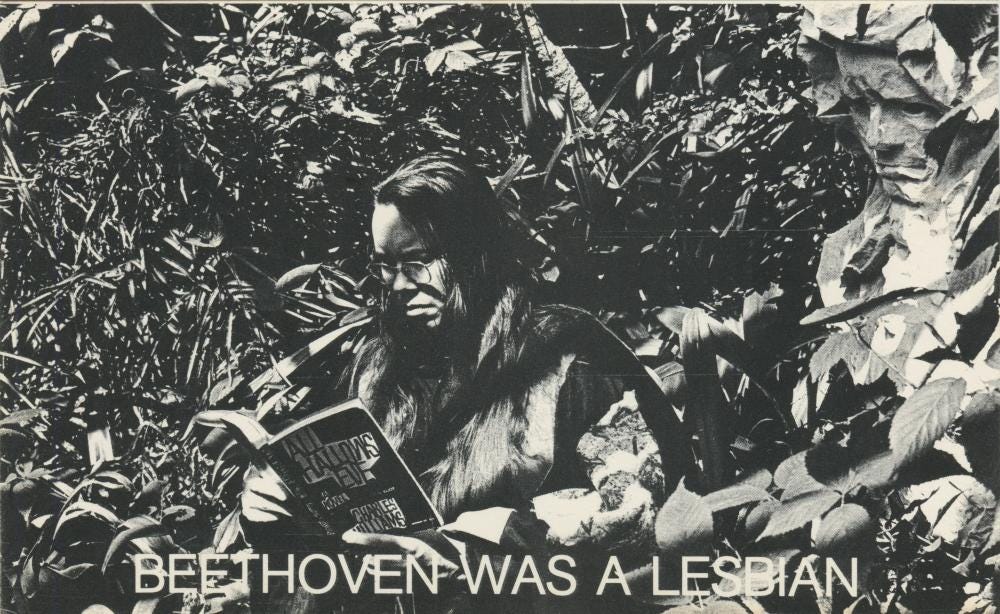

What has especially enticed me is how Pauline was empowered by her lesbianism and feminism while also maintaining a career in an outrageously male, homophobic, and sexist field. A Mexican-American butch dyke who took many lovers and refused to enter the closet, Pauline is a marvel—a woman who published “And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers” in the New York Times in 1970, one year before Linda Nochlin famously wrote "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" She asserted that Beethoven was a lesbian and inspired John Cage, who said, “Through Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening I finally know what harmony is…It's about the pleasure of making music.”

If I’m going to learn how to listen, I want to learn from her. It’s practically a Sapphic tradition, as many of Pauline’s sonic meditations are composed for group settings, having been initially developed and performed by an all-women’s ensemble at UC San Diego (her book of meditations is dedicated to them and Amelia Earhart). My group was mixed-gender over the weekend, but I could see how a dedicated space for women, especially during the early days of women’s liberation when women were finally embracing their bodies and discovering new ways to express themselves, would be an exciting and innovative environment to explore. Pauline traveled with these works and once introduced them at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, where 6,000 women participated in her Tuning Meditation in 1989. Participants sang “a tone from one breath with the option of tuning exactly to somebody else, or contributing a tone that nobody else is singing.” Surely it was an incredible experience—orgasmic, maybe!

Despite her great effort, Pauline contributed so much that even a two-hour documentary couldn’t cover everything. She worked closely with the women she loved—including musician Lin Barron, artist Linda Montano, and her widow, Ione—but there was barely enough time to explore how these relationships informed her work. I’m fascinated by how her ideas of deep listening may have influenced those partnerships and vice versa—and how intimate it might feel to practice in a room not filled with strangers but with loved ones or dykes, queers, and women. Pauline was not a separatist but understood the power of specificity and intention as expressed in lesbian and women-centric spaces.

I’ll be in Lesbos for her birthday on May 30th, fantasizing about a way to engage a group of dykes at the Queer Ranch festival to participate in an exercise in her name. Fifty years ago, Pauline cited Sappho as the archetype of women composers. As I trace the origins of Sapphic pop back to Mother herself, it seems only fitting to reconnect them as best as I can. We can try to send what Pauline referred to as “telepathic pitches.” She’d write to her friends to be ready to receive some—“I send them out once in a while.”

I’m listening, Pauline.