"OK, are you and your friends really that much better than these people?": A Q&A With 'Dykette' Jenny Fran Davis

The creator of High Femme Antics on how Rachel Maddow, Chloë Sevigny, and "Stone Butch Blues" became part of her queer reality show of a novel.

I’m not currently in a book club, so it’s rare that recently several friends of mine all decided to read the same book.

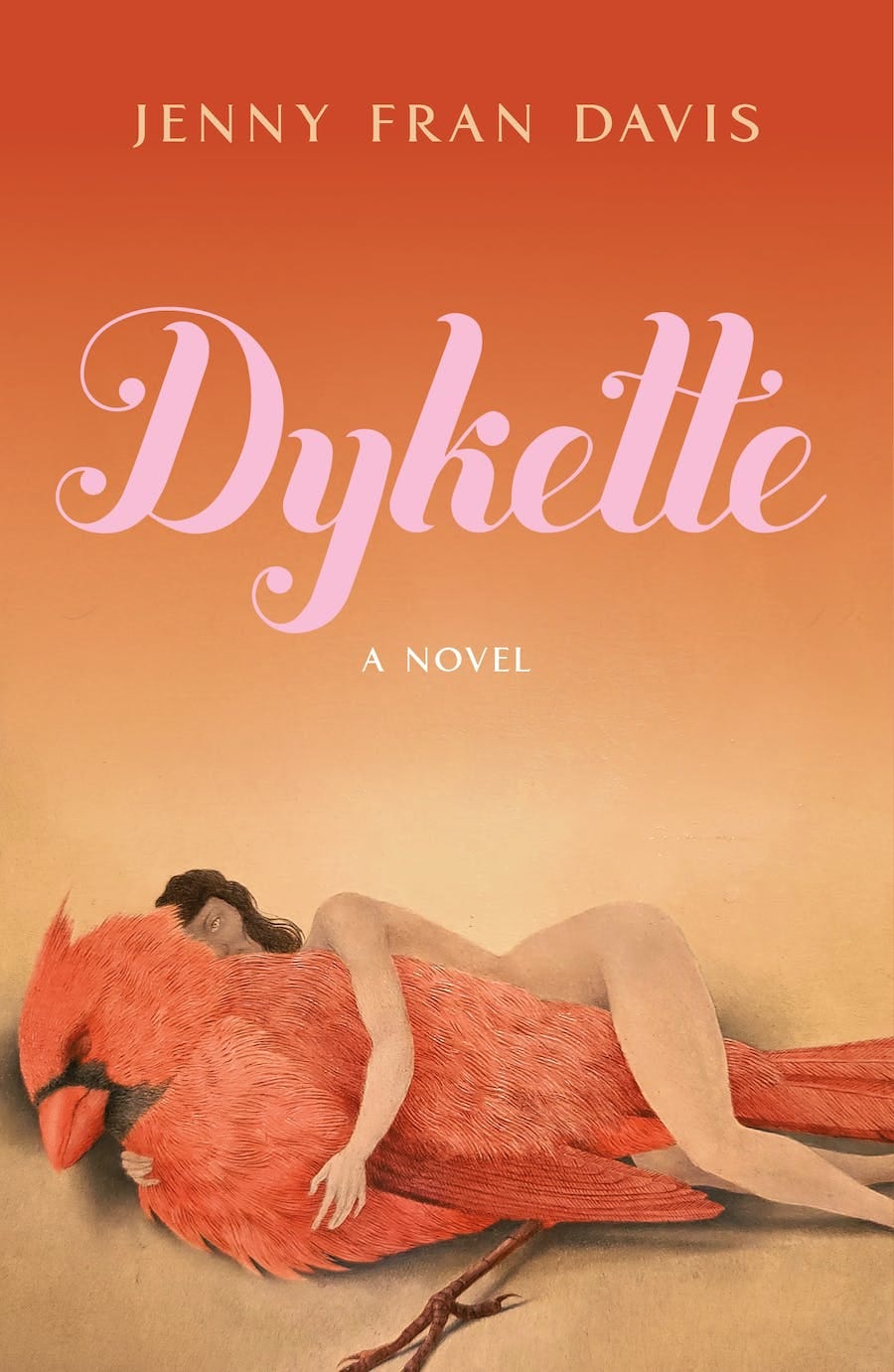

Maybe it’s the name — Dykette — that had interests piqued. One writer friend said she was “jealous” of the title, which I thought was very on-brand for this book in particular.

Jenny Fran Davis’s Dykette is filled with femme jealousy — a facet of what Davis’ coined as High Femme Antics in 2020. Other HFCAs include: “vintage methods of seduction — performing weakness, preying on tropes of midcentury femininity by acting and dressing like it’s the 1950s” and generally seeking validation and attention from mascs and other femmes, but particularly the former. Maybe you can see why this caused a stir on the internet — in a recent tweet, someone named Vanessa from The Ultimatum: Queer Love “the international ambassador for high femme camp antics” and they’re not completely wrong.

Dykette is a fictionalized adaptation of what first appeared as an essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books, following Sasha, a 23-year-old self-proclaimed dykette, defined in the novel as “Seen by butch. Seen as femme. … Containing both the butch’s gaze, and the femme’s stare. Because of course, they’re looking at each other.”

In Dykette, three femme/masc couples stay together in a Hudson Valley cabin for the week between Christmas and New Year’s. The owners are Jules, a 40-year-old Rachel Maddow-esque news anchor based on the MSNBC host herself, and her partner Miranda, a 38-year-old therapist who is currently being canceled on the internet. Protagonist Sasha (a thinly veiled Davis) and her butch partner Jesse are creatives in their early 20s, as are the third couple, Jesse’s friend Lou (who owns a general store in Brooklyn) and his girlfriend Darcy, a cool queer performance artist/influencer and the primary target of Sasha’s femme ire, especially when Darcy plans a performance piece adapting some of Sasha’s ideas and involves Jesse in some of the more intimate aspects. Intergenerational queer relationship dynamics play out over a 10-day spread of holiday theme nights, decadent meals, and heated sauna scenarios that I don’t want to spoil for those who have yet to read the book, which also integrates references to queer cultural touchstones like Stone Butch Blues, The Well of Loneliness and, most prominently, Boys Don’t Cry (Chloë Sevigny as Lana Tisdel: dykette)

What I loved most about the experience of reading Dykette is how many interpretations and questions it brought up around kitchen tables, in text messages, at an intentional meeting to discuss at length at L.A.’s local dyke bar. There are so many threads you could tug at to unravel the elements at play in Davis’ work, which is why it’s so challenging — the recognition of ourselves and the people we know, the imperfections of queerness, the complications of desires, and the horrors of facing our futures through someone else’s choices. Marriage? Monogamy? Jealousy at the expense of sisterhood or solidarity? What do we owe one another and why is it so painful to ask?

I want to keep having conversations about all of these ideas, and the Dykette himself Jenny Fran Davis was kind enough to kiki with for this week’s Lit Femme newsletter.

The funniest thing to me about this book is that the elder lesbians are 38 and 40.

When I started writing this I was 25, and 40 felt like the right age for the more established, wealthy job-having queers. I'm still only 28, but for some reason, now that I've made so many more friends that are about 40, I'm like, "Oh, OK — you guys do not have your shit together." I should have made them, like, 60.

This book came out of your essay, so how did you begin adding other characters to the world — like Jules, for instance?

Honestly, I think the impulse to write that character was fan fiction. For my whole life, I've watched Rachel Maddow on MSNBC, and the idea of taking someone whose image is so iconic that everyone can recognize, and easily imagine some version of what her life is like.

The two of us have never met, but I imagine a whole inner world and outer world and relationship just going off of a face I see on TV all the time. The idea of fan fiction was really interesting to me, and the recognizability of the face and the image and the eyeshadow on a really butch face. All of that was really fun to play with.

The inspiration was from real life: A slightly older couple — they probably were in their fifties — that my partner and I met at a Kentucky Derby watch party on the Lower East Side, like Sasha and Jesse initially encountered Miranda and Jules. We had this fantasy — they made this vague offer about us coming to visit them in Fire Island and we're like, "OK, they're our sugar mommies now. We're gonna totally keep this relationship up." And of course, the offer was kind of fake and never really happened. But I was like, "Well, what if, what if that was actually real in some way, and this older couple did take a real interest in a younger couple and really invite them to stay in their home for a week or two?" So I think the threads were definitely in reality plus an element of imagination, fantasy and fan fiction.

Rachel Maddow has always been, as someone who is attracted to masc of center people, one of few public figures that really represent that aesthetic.

Yeah. I've always felt exactly the same way. And when you see pictures of her from the '90s — she was an AIDS activist. She was so radical and cool. Something happened and I don't know what.

I was also really inspired by that informing the character of Jules. Like maybe she feels that she's sold out in some way. She's now on the liberal channel, performing for middle-aged people for her job, and has lost some of the radical punk ties to her youth. The old version of her and the new version of her are trying to reconcile both of those as someone who, again, has never met Rachel Maddow and probably will never meet her, but just projecting a lot of desires and regrets onto her.

I think maybe you'll appreciate this but one time in New York, my friend and I went to her partner's art opening and took pictures where you can see her in the background behind us.

Wow. I'm obsessed with her relationship. Did you see her iconic speech on tv?

Oh my God, the Covid speech? Yes, of course.

That was everything to me. The way she describes herself as a satellite planet orbiting Susan — like that is such butch devotional canon to me.

This is a wonderful segue into Sasha and Jesse. I just re-read your essay this morning and there really is so much of you and your relationship in Dykette, but translated into fiction. How has that worked for you? I can only imagine people that know you or think they know you in your relationship have different ideas about you now through your writing.

I decided to mention the essay in the book as a real-life tie-in — Sasha has written this essay that's gotten her bullied on Twitter or whatever. I kind of now see that essay as practice for writing Sasha and almost method acting as her. Because even when I was writing that essay, it's like people talk about in creative nonfiction — creating a persona, inventing a voice that's appropriate for whatever the piece is that's a separate entity from the narrator herself. I really felt myself doing that in the essay, and I think then when it got a bit of a reaction on the internet, I was like, "How are people saying or thinking that this is me? This is so clearly persona. It's so clearly a performance!"

Of course that performative part of myself exists, but I think with people who actually know me in my day-to-day interactions, that came across really clearly, so t was weird for people not to see that. And I think that was a big part of why I wanted to write a novel and not a book of essays or a longer piece of creative nonfiction. It felt really correct for that to be a character's voice. It felt easier to write Sasha than I think it would've been to sustain that performative sort of theatrical tone if I was really writing about myself.

I guess maybe not from the essay itself, but a lot of material from my life is apparent in the book. It's been kind of weird for friends to recognize themselves and things they've said. Luckily I feel like the characters are all really composites and no one I think should see a one-to-one version of themselves, which I think is good.

But it's been really interesting for people that I know to see a little bit of themselves and maybe wanting to see more or accepting that the book would be a faithful representation of our full friendship or relationship when it's a novel. Maybe I've directly quoted a hilarious thing that a friend said, but that doesn't mean that the character who said it is meant to fully represent that person.

It's funny because when you're writing realistic fiction, it's, it's really about observing the world and not making stuff up wholesale. So it's been really interesting to be more of an observational writer and base a lot of fiction in reality, and even seeing direct quotations or direct references to brands and objects and TV shows, and then to also sort of have that element of fantasy and unreal reality that's definitely based in observation and based in engaging with the real world as we find it, not with some imagined world, but also the work of the imagination in the process of taking reality and putting it onto the page.

Let's talk about the photo shoot. Friends who have published books recently feel that they have to come up with creative ways to do self-promotion themselves.

I have a good friend who airbrushes clothes, so all of the clothes we were wearing were made by my friend Alice. Luckily she was sort of underemployed at the moment and had a lot of time on her hands, so we just got together and as many blanks as we could find really cheap on the internet and holed up in the studio. I kept her company while she made a lot of hats that we also sent to media influencers. And I love to see you rocking your hat.

So fun. I don't even wear hats. That was a rare hat moment.

I love that. It looked great on you.

So then we were dreaming up ways to show off the clothes because they looked really good. I think a lot of it was just knowing that it was really on me to do anything sort of out of the ordinary or more creative than what the marketing and publicity team have the capacity for because they're working on a lot of different books. They're not gonna be planning a photo shoot for me.

We got a group together — the planning, of course, was very chaotic because it was raining that day, so we chose a span of a few hours that it wasn't raining. We'd just moved out of this apartment, but we had a really amazing backyard so everyone kind of just came over and went crazy and then it started raining at the end of the photo shoot so it sort of devolved into shoving wet cake into each other's faces. Everyone was wearing my designer shoes and I was under a massive Burberry umbrella, rushing out of the apartment being like, "OK, everyone who's in Prada or Dior or Miu Miu give me your shoes immediately and then go back to shoving wet cake in each other's faces." I had to do a little bit of damage control.

It sounds very on-brand.

It was really fun. I recommend doing that, for anyone who is publishing a book. I just think having a visual to share generates some excitement. I was lucky that one of the people who modeled for the photo shoots also worked as a stylist and everyone was able to bring in what they were passionate about and knew about. One friend was visiting from Minneapolis and ended up baking all these cookies 'cause she'd worked at a bakery. It kind of came together serendipitously.

You’ve said that you feel this is a very New York book — how insular do you feel the New York queer community is?

I'm from New York, so I think that also gave me a head start, but even just having full-time lived here for a little over a year, I do feel now everyone I meet somehow is connected to someone I already know. So in that way it feels small, but I also think that makes it feel big. Everyone I know also has a lot of people that I don't know, so it feels like there's always someone new to me, but rarely do those new people feel disconnected from the world that I already live in.

I also think New York is an interesting place because it feels like there's sort of an endless amount of people to meet and places to go and things to do. And in that way, you never really feel like you're at the center — it always feels like you're gravitating to new centers and finding a new little niche group of people, and maybe bouncing to another one. It doesn't feel so cliquey in that way. I guess there's a group of "It" queers, but I don't know — I feel like if you ask 10 different people, they would all tell you a different name for who's the aspirational it gay around town.

Sasha has been compared to Hannah Horvath from Girls. I see some parallels but was that a conscious choice or do you reject that?

I was mortified, and I think Sasha would be mortified by that comparison. I don't think they're similar. Hannah Horvath is certainly lovable in her own way. I don't think that she has any of the sort of self-conscious, theatricality and excessive sort of histrionic thing that Sasha has going on. I think Sasha has way better style and is way more perceptive and observational. I think Hannah seems a little bit more clueless and un-self-aware even though she writes essays. I think that's sort of the funny, dramatic irony of that character is that she actually isn't very self-aware, doesn't really read other people very well.

Sasha is more self-aware. Yes, she's clueless, but she plays up her cluelessness, I think probably in a self-defensive way, but also I think in maybe a radically vulnerable way, and I think that that's something that Hannah Horvath doesn't do. I think that comparison might just be that they're both sort of self-involved women. But beyond that, I don't know that it's a particularly strong comparison. I don't know that I identify with that.

I had some friends who said described the experience of reading Dykette as hate reading it because they hated some of the situations or aspects of the characters, and I think that's an experience where that I think some people had with Girls. Have you heard that from people — that they've 'hate read' Dykette?

Yeah. That's actually been maybe the primary way that many people have engaged with it, which is great. How else as a gay person are you supposed to read a book called "Dykette"? Of course that's the way that people read it and I think that can only be expected.

I think that's a fun way to read. I often consume books that way, mortified by how much you identify with the characters, projecting a lot onto certain characters and really hating them because of that. Or maybe there's a gay person in your life who's treated you that way, and so I think there's been a ton of that.

I think that was something that I was primed for because that's how a lot of people read the essay. That's maybe the reason that it was triggering for people — they recognized either themselves or other people that they know love/hate in their own lives. It's been funny to see that and, and pretty enjoyable. Something I've been thinking about is the way that people have immediately called all the characters 'despicable' or 'uncomfortable,' 'awful' or 'selfish.' I'm just like, "OK, are you and your friends really that much better than these people?" Because I would guess that you and your friends are not so superior to these people and just because they're not presented as gay people who are aspiring to moral goodness doesn't mean that they're despicable terrible people. The only part of that sort of read that I question is the jump to "These people are terrible. They only exist to evoke our hatred and spite and pity," which I think definitely there's some of that, but also maybe there are parts of these characters that we can empathize with or even sympathize with.

One thing I was thinking about in terms of Sasha's relationship with Darcy — do you think that Sasha identifies as a feminist?

That's a good question. I think in basic ways, yes. I think that she maybe imagines herself to live in a more post-feminist reality where we can all assume basic truths about gender equality and all the big things. I bet Sasha's on board with all the big boring issues like abortion and equal pay — all of those sorts of things. But I think that she sort of delights in doing these anti-feminist performances that I think sort of play on and expose fundamental discomfort with her own femininity. And I think a big part of the way that she engages with and interacts with her own femininity or girlishness is to sort of play up tropes of being a hysterical woman and a jealous woman and a possessive woman. Like a nagging wife and a devoted housewife, sort of inhabiting, in a pretty unstable way, all of these tropes — these sort of anti-feminist icons.

But I don't know if that means she's not a feminist. I think she doesn't accept and aspire to gender equality, whatever that means. She's troubled by gender and loves gender and really delights in a lot of gender play. So I think feminism might be not as much of a concern for her. I think she almost thinks about it too much to just call herself a feminist.

Tell me about the choice to include Chloë Sevigny and her character in Boys Don't Cry.

In real life, I have an old dress of Chloë's. This whole thing about being in the same place as Chloë' when I was wearing it never really happened, but I think that's another sort of fan fiction fantasy, the impulse to be like "What if I ran into Chloë' while wearing her dress?" And of course that happens to Sasha.

I think the Chloë' thing in particular just feels rich in character — the character of the celebrity Chloë' Sevingny, but also the character that she plays in Boys Don't Cry, in terms of iconic women and iconic cool girls and this whole thing about being cool being girly and cool at the same time. That's more fascination with Chloë', the actress, and then when Chloë' plays this really iconic femme in Boys Don't Cry, the two sort of converge. That's why I am really fascinated by that moment, and I think why Sasha watches that scene a million times. It's seeing this butch femme dynamic come alive that's so much about being a girl, but not being a straight girl, and being absolutely aspirational, iconic — like, Chloë' is everything in that scene and everything in that movie, and to be everything is something that I think that I and Sasha are really fascinated by. How can someone captivate and capture and absorb all of the like iconicness in the world?

Chloë herself is just obviously an object of fascination. But then sort of layered with Chloë' as this amazing femme in this movie, I think it's exponentially more delicious and rich to explore. And yeah, having her real dress in real life has also been a journey. I've only worn the dress one time, but it's in my closet in a very special spot. Just knowing that it's there does a lot for me. I guess it's just like the object pervert thing, another way of getting to that.

A friend of mine said that reading this book kind of felt like they were watching a reality show. What do you think about that idea?

Love that. I love reality TV and even though maybe it wasn't so conscious of writing it like a reality show, I've watched so much reality TV that of course it's seeped into my consciousness. And I think they have mastered storytelling. I can't watch scripted TV because I'm just not interested. But a reality show, what could be better? The way that they use music and B-roll and confessional and all of these things — it's an art form. And I think that the people at Bravo and TLC or whatever have completely mastered it. I'm addicted to it and I think, yeah, maybe sort of consciously, the way I wanted to tell this story was in a way that felt like reality TV, like a gossip obsession, a sort of delicious dessert that like, yes, if you watch too much of it, you'll get a headache and you'll feel crazy, but while you're in it, there's this sort of adrenaline rush. I think sort of just wanting it to feel sugary and sweet and over the top and addictive was really on my mind while I was writing.

There's a lot of humor in Dykette. Are you a naturally funny person or is that something that just comes naturally or that you wanted to lean into?

I wanted it to be funny because I feel that a lot of gay media and gay books are really humorless. And I think maybe I overcorrected a little bit too much trying to find humor maybe where I should have instead found more genuine pathos.

I don't know that I'm a hilarious person, but I do think that humor is extremely important to me. All of my friends are really, really funny. I gravitate towards funny people. It's my main coping mechanism. I'm always looking to laugh. I laugh when I'm uncomfortable. I laugh when I'm sad. Humor is a part of my psychology and way of interacting with the world. So it was important to me that the book had levity and humor. I wanted there to be almost absurd, yet hilarious asides, entries into Sasha's mind that felt uncomfortable, but also really funny in a way that she's not so polished or put together for the audience. Just a real glimpse into the mind of a girl who's going crazy.

I'm always surprised by the things that people find really funny and the things that they don't catch. And it's never the same person to person. Things that I intended to be funny I'm sure many people didn't even notice.

Tell me that your partner actually, in real life, made a harness in a leather-making class.

So they went to a leather-making workshop — it was taught by this guy who runs an accessory school in Italy. And, of course, now that's the dream. My partner also works in film — they're a set decorator, so the strike has been huge in our household. I'm in solidarity with all of the other union wives who have their husbands home with them 24/7. It's really hard for us and we have no money. Like he needs to go back to work immediately.

But yeah, the accessories school really exists. This workshop was actually part of a Dyke Soccer community event back in like 2018 maybe.

And there was actually a harness made.

Yes, it's in a box somewhere, but it exists.

The Chloë dress has a special spot in the closet but the handmade leather harness is in a box somewhere?!

Maybe we should frame it.

I'm saying! I wanna see a picture.

OK, I'll take a picture though. I'll send it.

You use various pronouns for Jesse in the book — did you get any pushback on that?

I didn't. The only slight question I got about that was from the copy editor, and that's very normal because it's their job to find inconsistencies and make sure there's a logical reason for any inconsistencies. But all I had to do was say, "That was intentional. Trust me, I've thought about them." And then they were, they were totally accepting. feel lucky about that because I think maybe with another editor or another publisher, there would've been more pushback or more concern with 'how will the mainstream reader be able to tell who you're talking about?' It luckily wasn't an issue and it was also actually something that happened more in revisions than it did when I was selling the book.

What about the title? Just because "dyke" can be so fraught sometimes.

I was really worried that they would make me change it, but I think that it was actually a selling point. They knew that the title was provocative and evocative, and I think they knew that it would be would more attention-grabbing and hopefully lead to more sales. Also what else would they change it to? It's the title. It just is.

Luckily there was no conversation about it. I was always waiting for there to be. When it came time to put the galley together, I was like, "OK, now they're gonna wanna talk to me about the title," and they didn't. And then the next thing, meeting with the marketing people, "They're gonna wanna talk to me about the title" and then no one really said anything. It hasn't been flagged, I think, because of the "ette." It's diminutive.

Tell me about figuring out the ending of this book.

I don't remember at what point in the process I decided to have the whole thing with the ring and the sauna, the ring meant for Miranda that Jules was gonna use. I knew there was gonna be a proposal. I knew that Jules was gonna be planning to propose to Miranda and then Sasha and Jesse would sort of thwart that plan somehow. And I think it took a few passes working through the ending to really work out all the details.

It's so funny because in fiction there are so many logistics that you have to account for. It has to feel believable, and I'm often wanting to be like, "Just go with it — it'll be fine." I just knew that they were gonna ruin the ring somehow, but then you actually have to figure out exactly how that's gonna happen and feel realistic and feel believable and feel like it's really something the character would do, and that it's really possible for a sauna to get that hot and that the ring really would be floating in the pool of water, you know? All of these annoying little pesky questions that I never wanna deal with when I'm writing. I'm sure there's many things that are implausible, but to my knowledge, sure, that works.

I think also just because so much of the book is the characters contending with what it means to be normy or mainstream gay people who are gonna get married and have these domestic fantasy lives, that Sasha and Jesse think that Jules and Miranda have. I guess the idea of marriage and a proposal seemed just like a very natural climax to be building towards. Not just for Miranda and Jules to be sort of aspiring to marriage, but then also Sasha and Jesse as this younger, more dysfunctional couple trying to figure out if they're on this normy marriage track or if they're kind of veering towards something else that's a lot weirder. And then for them to physically confront this ring, this symbol of monogamy and domesticity, and to have it all go awry, I think just felt right. But definitely not something that I decided beforehand. I think it came about through revising and reworking the logistics of what had to happen because it's in the realm of reality and not a fantasy book.

OK, one question I had was how could Jessie not think that Sasha was gonna flip her for sewing Darcy's ass [as part of a performance piece]? Like what, in what world?

Well, yeah, I agree, but I think there is some doubt that that really happened in Sasha's mind. And I think that's definitely what she sees, but I wanted there to almost be a sense of, is she imagining this? Or did this really happen? And of course, then they have this huge fight and Jesse sort of owns up to it. But I think it's maybe his little act of rebellion. He feels so stifled. He feels like Sasha's always getting to have these big hysterical, dramatic moments, and I think he wants that for himself and he gets really caught up in the moment. He wants to be provocative. He wants to toy with her the way that she's always toying with him. There's a self-destructive part of him that comes out in that moment that he immediately regrets. But of course, he doesn't have the self-control in that moment to not do it.

One of the things that I really loved about the book was the way you use queer texts like Faggots and Stone Butch Blues and The Well of Loneliness.

I think a lot about the idea of a syllabus that we all kind of work through when we realize that we're not just gay, but interested in the project of being gay and the lineage of our gayness. And I felt that, for these characters as people who are both gay and interested in what it means to be gay and what it has meant to be gay, historically, they would be reading all these things, and all of these books just really seep into your own formulation of identity and how you talk to people and how you talk about the contemporary moment and your place in the longer history of being gay and all of that.

So just something I've noticed is that these books, especially Stone Butch Blues and Well of Loneliness and even The Argonauts, which was published in 2015, has become a big part of the conversation. But I also think there are these cultural touchstones that at face value are not gay, like The Sopranos or Real Housewives of New Jersey or Magic Mike, these iconic things that are not made for us, but we have claimed them as our own. I have embarked on this project of making them into gay touchstones, gay media, gay iconography, and identifying with the characters in them. They've worked themselves into our little subculture, too.

Our lives are filled with so many references. We're always watching and reading and that's just such a massive part of the way that we come to understand ourselves, see ourselves, and see other people. So much of the book is about the way that the objects in our lives and the TV shows we watch and the books we read come to stand in for our identities or who we are. Not in a bad way — in an inevitable way. So I think it was a convenient way for me to be more specific about how that happens.