Mothers of the Sexual Revolution: Early Queer Feminist Comedians

Uplifting the early dykes of stand-up (and sit-down) comedy: Madame Spivy, Moms Mabley, Frances Faye and Rusty Warren.

Over the last four years, I had the pleasure of working on a new documentary out today on Netflix called Outstanding: A Comedy Revolution. In part, the film tracks the history of queer and trans-stand-up comedy in America, and it was my idea of fun to delve deep into its historical origins to a time when the fusing of comedy and music was a prized combination. Defining “stand-up” comedy that far back is as intricate a task as defining a queer person’s outness at a time pre-Stonewall, when things were necessarily under wraps.

Outstanding celebrates Robin Tyler as the first openly gay comedian who referred to herself as a lesbian in public, performing with her then-partner Pat Harrison and simultaneously shouting into mic and megaphones on the stages at Gay Freedom rallies in the 1970s. Like most of the early queer performers, Robin got her start with a little bit of music, too — in the ‘60s, she could be found among the drag kings and queens at Club 82 doing Judy Garland impersonations.

Robin’s predecessor Moms Mabley appears in Outstanding, and there are glimpses of other early comics, but one of the greatest aspects of doing research into anything of this nature is tugging at a thread and finding all the places it’s been cut by the queer teeth of lesbians who quite literally set the stage.

Before 1969, being out was still a private affair for even the most butch of women, like the celebrated Moms. Moms got her start on the Chitlin Circuit, but I was also chuffed to find out that among the various venues she played in her lifetime, one was the penthouse club of her friend Madame Spivy at the corner of Fifty-Seventh St. and Lexington Avenue in Manhattan.

In the 1940s, the Brooklyn-born Spivy La Voe (who has been described as “a large handsome woman in white” and “the bulldog bulldyke”) ran her club how she wanted. She was said to suffer no fools, kicking people out at her leisure, no matter if it was closing time. She’d get behind the piano and sing tunes from her 1939 album, “Seven Gay Sophisticated Songs,” including lines about women dancing in drag (“Oh she did the tarantella with a colorful umbrella and in her hat, she wore a quill / She dressed up like a fella in a suit of real bright yellow just to give the audience a thrill”), and references to pansy cats, bearded ladies, and faeries. She booked the likes of Mabel Mercer, Thelma Carpenter, Martha Raye, Carol Channing, Bea Arthur, Liberace and Paul Lynde. Judy Garland and Patricia Highsmith were among the regulars, as were her paramours like Patsy Kelly and Tallulah Bankhead.

To Spivy’s credit, she booked her sisters in Sapphistry, like Mabley and Frances Faye, both women out to those in the know. Similar to Mabley, who did character work in a few early Hollywood films, Spivy found boosted fame with small parts in films like The Manchurian Candidate and The Fugitive Kind after making her on-screen debut in a 1959 episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Eventually, her acting career led her away from music and her club to Los Angeles, where she remained until her death in 1971, two years after the historic weekend that was Judy Garland’s funeral and the Stonewall uprising.

Fellow Brooklynite Frances Faye was on screen, too — most notably performing alongside Bing Crosby and Martha Raye in “Double or Nothing,” and, later, toward the end of her life, as the washed-up madam sharing scenes with Susan Sarandon and Brooke Shields in Pretty Baby. Though if you’re an xennial, like me, you might have more recognition of Faye’s queer family tree tune that is “Frances and Her Friends” from Season 1, Episode 12 of The L Word.

I know a guy named Willy,

Willy goes with Tilly

Tilly goes with Milly

What a ball!

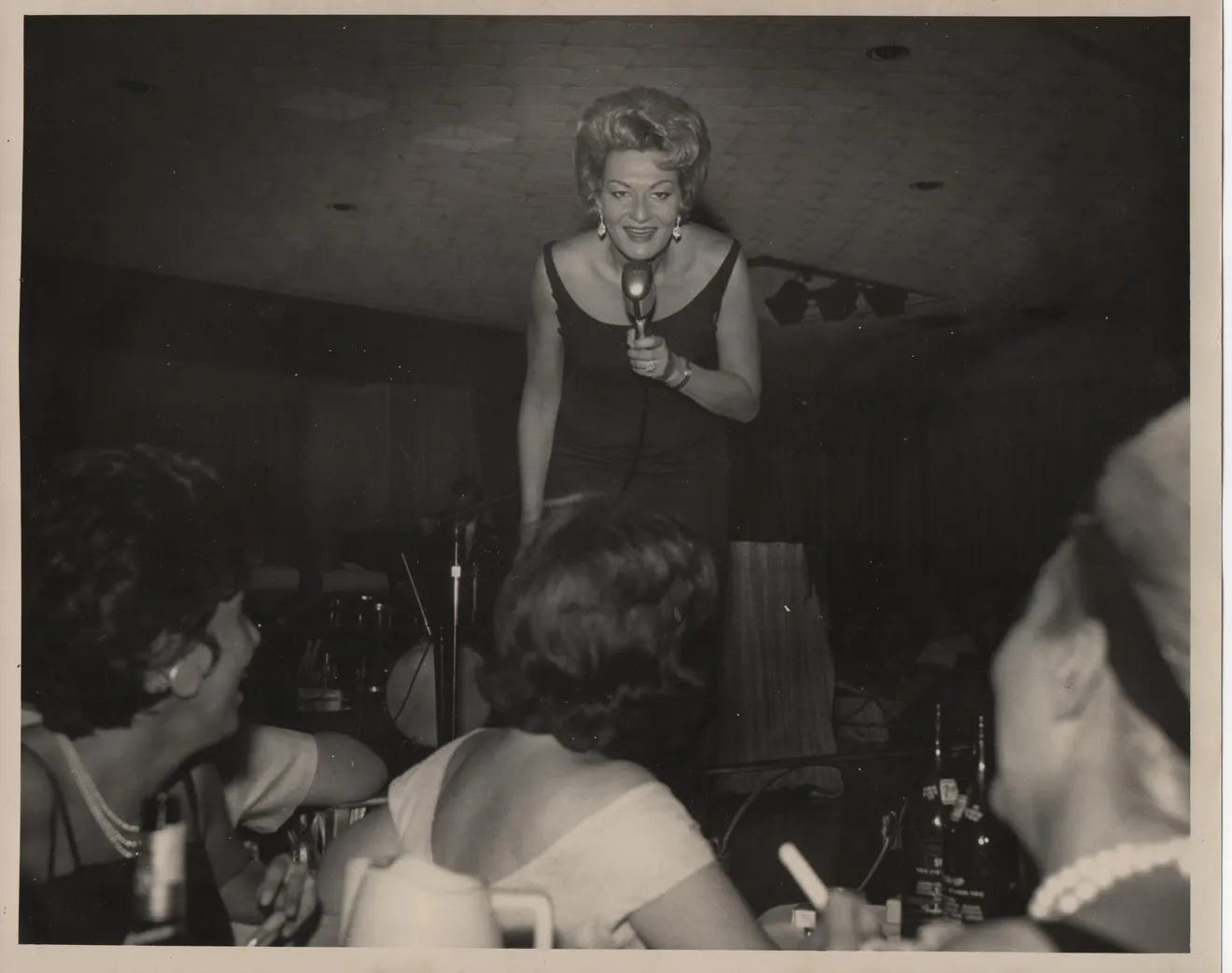

Acting was fine, but Frances much preferred live performance. She’d been playing spots like Harlem’s Cotton Club, Chicago’s Chez Paree, and London’s Paradise Club since she was a teenager in the 1930s, and over her lifetime, she recorded 15 studio albums. Her comical cabaret songs played well to audiences on both coasts and cities in between, rhyming her own name with the era’s use of pre-pejorative “gay.” ("Frances Faye, gay, gay, gay, is there another way?")

On her 1946 self-titled debut album, Faye also paid tribute to gay singing satirist Bruz Fletcher, who killed himself four years prior after being the target of tabloid gossip. Frances became the first to record his queer love ballad “Drunk With Love,” the recording one Marijane Meaker remembers playing at L’s, the Village dyke bar where she first met Pat Highsmith. It was quite a queer world if you knew where to “go, go, go,” as Frances would sing, and listeners roared with laughter and delight.

Frances had a hard time getting radio play. Her 1952 single “She Looks” was deemed too scandalous for its rather benign line, “She looks as though she is but isn't.” Then there was the problem of her appearance. She wasn’t considered especially attractive, and she kept her hair boyishly short at a time when that was simply uncouth. Still, she worked consistently, and though she was less of a household name, she became respected as a performer’s performer. By the late '50s, Frances had made fans out of the likes of Irving Berlin, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe and Frank Sinatra. She played sly songs like “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate” on The Ed Sullivan Show, and while she found ways to slip her androgynous lover’s name into songs on air, she bemoaned the femme drag it required for her to be television-ready, wigs and gowns and all.

It was in clubs like Spivy’s or, later, the Crescendo on the Sunset Strip that Frances could be more herself and get schticky with mixed crowds of dykes and fags and friends. A clip from the 2001 Bruce Weber documentary Chop Suey shows Frances responding to a shouting woman audience member with the quip, “That’s why I never go with girls — they’re so aggressive when they’re drinking.”

The press and even Faye’s Caught in the Act album art referred to her long-time partner Teri Shepherd as her “secretary,” but in a still rather subversive context for the time, Frances’ bio read that she "resides in a hillside home high above the famous Sunset Strip in Hollywood which is shared with her secretary and four French Poodles.” Frances was coded, but anyone who saw her act would get the message.

A tragic 1958 hip injury stalled Faye’s career and ultimately affected her ability to perform for the rest of her life. When she died in 1991, the Los Angeles Times named Shepherd as her “friend and longtime companion.”

Right as Frances was cruelly taken out of commission, Rusty Warren was having a moment with her hit joke track Knockers Up. A lesbian in her personal life and a stealthy feminist on stage, Warren got her start tickling the keys at lounges in Boston and the Catskills, where her banter went over better than her playing. She found that audiences responded to her punchy point of view, got a manager, and leaned into the kind of material that got her tagged as blue and bawdy despite her tameness by today’s standards.

“I like helping inhibited females enjoy themselves,” Rusty once said of her act. “Knockers Up” was a rousing call for women to puff their chests and march with pride. No surprise that the men didn’t mind one bit. That was Rusty’s talent — razzing both men and women to laugh at the absurdity of heterosexuality without them realizing it.

Rusty, at one time referred to as “Mother of the Sexual Revolution,” couldn’t get booked on television, so it was even more awesome that the LP became and remains one of the best-selling comedy records of all time. A party album, listening to Knockers Up became a special event — something to be enjoyed among friends. Despite the millions sold, that Rusty was willing to speak about sex and gender so blatantly in the early 1960s was enough to have her labeled “For Adults Only.” Her material kept her from performing on late night with Johnny Carson, much less anywhere less chaste.

Rusty recorded 15 albums between 1959 and 1977, playing the lounges of the Aladdin and the Sahara in Las Vegas or the Dunes in Ft. Lauderdale to tourists and members of her Knockers Up Club (at one point, 300,000 members strong.) Listening to her material now, it’s easy to see how integral Rusty was to the ideas of sex positivity and feminism several years before women’s liberation. It’s no surprise, then, that the press was unkind — a 1963 Time magazine article criticized both Rusty and her fan base, writing that her crowd was full of “jolly, plump, graying matrons dying to see their goddess,” lamenting that “they made her a $5,000-a-week nightclub star, outdrawing Mort Sahl and Shelley Berman.” (Boo hoo.) When Rusty sold out a local venue for weeks on end, The Chicago Tribune similarly brought her down, writing that she “takes her gigantic lack of talent to brassiere sizes, prostitution, infidelity, pregnancy and several similarly hilarious subjects,” as if these subjects weren’t ripe for wit.

(It’s not likely to surprise you that both reviews were written by men.)

For her bravery, Rusty faced censorship, sexual harassment and violence, but she found kinship in fellow performers like her inspiration, Sophie Tucker, as well as peers-turned-friends Belle Barth, Totie Fields, Eydie Gorme and Pearl Bailey. By the time the sexual revolution rolled around, the kind of innuendo Rusty was famous for was the least of men’s problems, and the women were galvanized elsewhere. Performing less and less frequently into the 1980s, Rusty retired and relocated to Arizona before, eventually, Hawaii, where she lived with her partner Liz Rizzo for many years, as noted in her 2021 New York Times obituary. It was the first real acknowledgment that Rusty was gay, surprising many fans who might’ve assumed her heterosexual based on how much she griped about men. (Wink, wink.)

Even though Rusty wasn’t out on stage, her radical refusal to tone down her act and power to make the nation’s women rise proudly together from their seats was proof positive that there was a thirst for comedy paralleling women’s experiences, putting words to feelings that they didn’t necessarily feel they could voice themselves. (Consider that Knockers Up came out three years before Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique blew the lid off the boiling pot from the stoves of simmering, suffering housewives.)

Even if new generations are unaware of these women’s pioneering influence, the early work of queer comedic performers has made for a far more interesting landscape of humor and cultivated the communal aspect that is, IMHO, one of the best parts of Outstanding. And now, I can’t watch Debra play the Palmetto on Hacks without thinking of Rusty Warren, who won over every crowd who dared to see her on the strip. Catherine O’Hara famously spoofed Rusty as a singer called Dusy Towne on SCTV, including a holiday special with John Candy playing Divine — queer indeed. Drag comedienne Lypsinka performed “Frances Faye and Friends” in her hit one-woman show, “The Passion of the Crawford” in 2014, while Mx Vivian Bond covered Spivy’s hangover-themed song, “I Didn’t Do a Thing Last Night,” during a pandemic video performance. And as seen in Outstanding, Moms Mabley has been played by Wanda Sykes on The Marvelous Ms. Maisel and on Broadway by Whoopi Goldberg, who also made a documentary about her hero in 2013: Whoopi Goldberg Presents: Moms Mabley, now available on Max.

I’ll leave on this note from Frances Faye, singing “My Last Affair.” Reading the lyrics, you couldn’t possibly get the same feeling you might from hearing Frances emphatically protesting love so much. It was all in the delivery, and Frances, like the best of queer performers, knew how to deliver.

Can’t you see what love and romance have done to me?

I’m not the same as I used to be

This is my last affair.

Tragedy just seems to be the end of me

My life is misery

This is my last affair.