I’ve never been the type to fall for straight girls, but Elizabeth Wurtzel may be an exception.

Last month, when I was working on a story about the Indigo Girls’ triumphant legacy with a song like “Closer to Fine” (as celebrated in Barbie), I remembered how it was Elizabeth Wurtzel (most well-known for her dark confessional memoir Prozac Nation) who first called out the freedom lesbian musicians like Amy, Emily and Melissa Etheridge exalted. In a piece called “The (Fe)Male Gaze” for the 1996 collection Surface Tension: Love, Sex, and Politics Between Lesbians and Straight Women, Wurtzel (a rock ‘n roll writer who got her start famously writing that Lou Reed should have been dead, by rock legend standards, 30 before he died) praised openly gay women musicians of the ‘90s for their lesbian aesthetics. Wurtzel writes:

"I don't mean that they had dykey layered haircuts (though they did) or that their physical presence was boxy and mannish (though it was) or even that their intermittent chatter was laced with references to Sapphic icons like Virginia Woolf aad Audre Lorde and Radclyffe Hall (it wasn't.) It was more a total quality that emanated from the stage, a full-bodied and even excessive expression of unshackled emotionalism, of unfettered need and shameless want — this concert was a son cycle of liberation — that could only be a product of a world, to paraphrase Heminway, women without men. There was something about the Indigo Girls' music, and particularly their live performances, that just had to be the result of divorcing one's mind and one's sexual concerns from the opinion — perhaps even the gaze — of men."

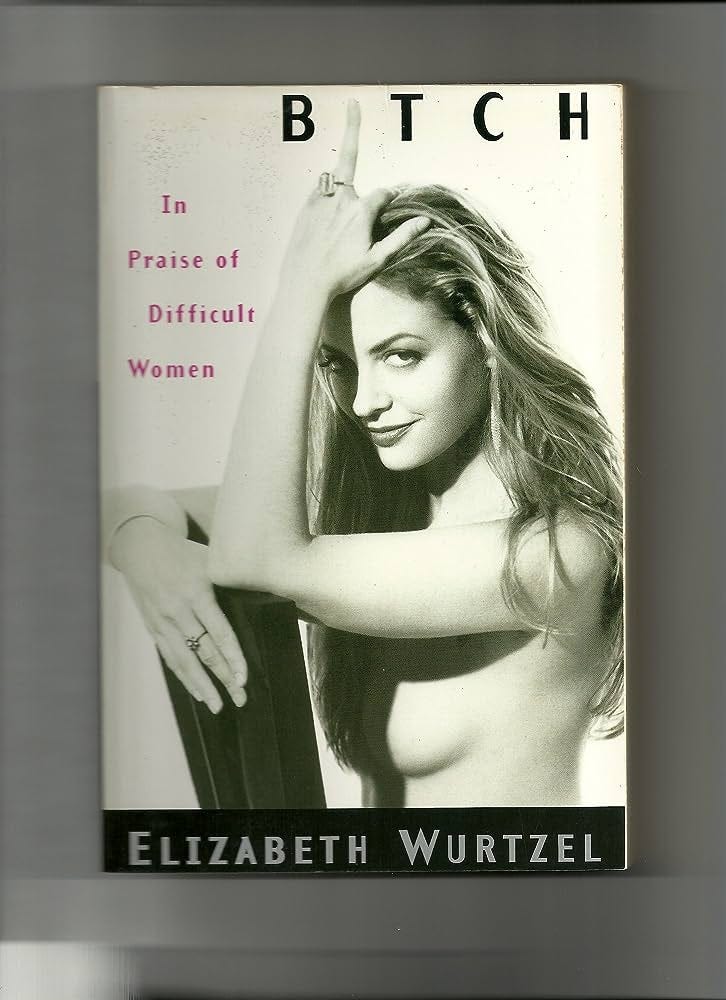

Coming from a self-professed straight girl (who expertly employs the word ‘Sapphic’ despite writing she’s never had any experiences in that vein), praise of lesbian musicians for their “emotionality” as “expressions of strength,” their unabashed willingness to forgo concerns of how men will receive their “overwrought and emotionally needy songs” was one of the best things I’d ever written about “women’s music.” Even when Elizabeth (nothing if not opinionated) wrote things I didn’t necessarily agree with, her strength was in pointing out the contradictions and complexities of artists, individuals and humanity, including herself. Her work rails against types in her iconic book Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women, using Courtney Love and Alanis Morrisette as examples alongside Amy Fisher and Hillary Clinton, and, perhaps most importantly, she was never afraid to call herself a feminist, even in the Backlash era of the Reagan ‘80s when, by all accounts from Prozac Nation, she wasn’t always acting like one.

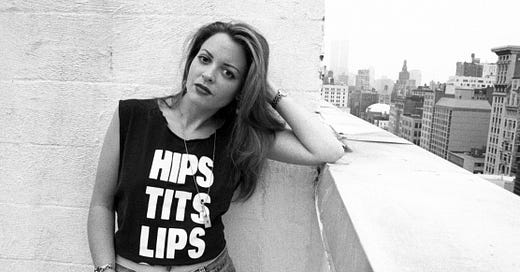

Elizabeth Wurtzel died prematurely in 2020 at the age of 52. Last year, her things were quietly auctioned off in New York where she’d lived most of her life, but her archives have yet to find a home, at least that’s been made public. Despite the many addictions and mental health issues she struggled with throughout her life, Elizabeth never stopped writing, even when it seemed the world was telling her to shut the fuck up (which they often did). She’s credited for bringing the first-person confessional style to prominence with the success of Prozac Nation upon its first printing in 1994, but with it, received just as much shit slung at her for being a navel-gazer; a self-obsessed privileged white girl who dared complain about her life as a Harvard co-ed. No matter how many bad reviews about the book were published, Wurtzel kept writing.

“I’ve often felt like I don’t need anybody else to be on my side because I’m on my side,” Wurtzel once told Liz Phair in a conversation for Interview. “I do think that’s unusual in people, but I think it’s especially unusual in women.”

Elizabeth Wurtzel’s feminist lens (particularly in music journalism) was not without credit to her predecessors. Her short-lived gig as The New Yorker’s pop music critic made her a direct descendent of Ellen Willis, another hetero-feminist writer whose support of queer women and their performances of liberation were significant and validating in the 1960s and '70s. When Wurtzel cites Willis’s work within her own in Bitch or elsewhere, it’s then I find myself falling for her, the way she made it appear so effortless to write so much about oneself without it being a solitary act. Her love for other women — especially other women writers, thinkers, and creatives — was not lessened by her love of men — and she loved her some men, particularly Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan. Ironically, Elizabeth’s talent was in making me actually want to read about the music of men, because I trusted her to tell the truth about them.

Most people think of Elizabeth as she was in the ‘90s, which was why her death from cancer was so shocking and nostalgic — where had she been this whole time, anyway? For anyone paying attention, she was, of course, writing (among other things, like becoming a lawyer, getting married, going through chemotherapy). A piece she wrote for Tablet in 2013, “In Bed With Bob Dylan,” is one of my favorite things she’s written. What starts out an ode to Sundays spent listening to Bob Dylan LPs turns into a record of her way of experiencing music which, I find similar to mine despite the circumstances being different.

“I have never been turned on to music by a boyfriend, because only stupid girls listen to what men do and don’t figure it out for themselves,” Wurtzel writes. “The longer I live, the more it looks like the world is full of stupid girls. Some of my best friends are stupid girls. Men email me YouTube videos to watch all the time, and the more I like them, the more I don’t click the link. So there.”

Whenever Elizabeth wrote about music, she was writing about herself, and when she was writing about herself, she was writing from a place of ownership and discovery — of being a feminist, a difficult woman, a bitch. She’s been called a rock ‘n’ roll writer and yet her work in the music realm is less celebrated, less remembered — uncollected and scattered between The New Yorker (where Tina Brown swiftly fired her upon assuming the reigns), New York Magazine (where she wrote a regular column called Sounds, including a rave review of Sinead O’Connor’s second album) and out-of-print books like Surface Tension (thank God for the Internet Archive).

“I learned to write from rock ‘n’ roll,” Wurtzel wrote for Tablet. “I never thought people were choosing between reading one of my books or another author — I thought it was me or Madonna or Hole or whatever was going on at the time. I could never figure out why I was cursed with the worst voice and would never be a rock star, which was obviously what should have happened. I wanted to be on the cover of my books, because that was how albums looked.”

The hardcover cover of Bitch had Elizabeth sitting nude, backward on a chair with half of her face and both of her tits enshrouded by shadow. She’s got her middle finger thrust into the air (putting the “I” in “bitch”), a sly grin of a gaze, seducing the reader and telling them to fuck right off at the same time — rock ‘n’ roll woman indeed. But her publishers got nervous and the paperback cover was changed to a close-up of her face.

"The publisher was nervous about the cover being too offensive," an anonymous source told Salon in 1999. "The response from the bookstores was poor. The book wasn't doing too well, and some thought that the cover was just too much."

But that was Elizabeth Wurtzel — too much. Even those who knew her would attest to it. The film version of Prozac Nation, while not well-crafted, was held from release for several years due, in part, to the unlikability of the main character who was, of course, Elizabeth Wurtzel (as played by Christina Ricci). Of course, men found Elizabeth to be too much, but other women, too — not the bitches she gives credence to, but the safe ones, the scared ones, the “stupid girls” who, unlike the Indigo Girls or Melissa Etheridge, give way too many fucks about what dudes will think about the freedom they crave. That kind of self-expression is too dangerous for those girls, who find the Elizabeth Wurtzels of the world to be distasteful without the ovaries to ask themselves why.

In her 1992 New Yorker piece “Girl Trouble,” Wurtzel wrote about the women of early ‘90s rock that were born out of Patti Smith and Madonna, bands like L7 and Hole.

“By the time you’ve listened to all of Pretty on the Inside,” she writes, “you’re likely to go from thinking that Courtney Love is a freak of nature who needs to take voice lessons to having a real sense of empathy with her.” Of the song “Loaded,” she finds “once again it seems that, in the conflict between pride and shame, pride definitely wins out.” Sure, she was writing about Courtney Love, but also — per usual — about herself.

What I appreciated most about what Elizabeth Wurtzel does in “The Fe(Male) Gaze” is not her praise for lesbians musicians solely on the basis of their being so explicitly gay, but how she could locate herself — a straight bitch — in their music. Wurtzel played a little guitar but couldn’t carry a tune, but were she the rock star she wished she’d been, she writes, "There would always be some guy, imaginary or real, whom I would be singing to, and I'd always have to wonder how all of this was coming across to him. If I ranted and screamed, If I let out all the ugliness and horror that I feel, would he still like me?"

Elizabeth’s was always an honest take, no matter how her own thoughts or feelings might complicate her feminism. She wrote into those complications, embraced them as challenges, and her writing was better for it. It makes for a more pleasurable reading experience, getting that kind of access to someone who isn’t afraid to explore why she wouldn’t fuck Amy Ray, but instead, gave her “a new idea” on how to be a female performer: “how I could be controlled and crazed all at once, how I could own that distinctly male rock star quality that allows all the ranting and raving to project itself onto desire instead of need, into a catcall and not a caterwaul."

Elizabeth ends the piece back where she started — an audience member discovering the power of identity through the transformative nature of rock ‘n’ roll, witnessing herself where she’s not entirely welcome, shameless and proud nonetheless.

"To experience the transformation of coming out has got to create a break with the past like nothing I will ever know,” Wurtzel writes. “No matter how many outre things I manage to do with my life, how many body piercings of tattoos or whatever else I might litter my body with, I am still, as a sexual being, the girl my mother wants me to be, the woman who is obedient to the male gaze. And Amy Ray, I am certain, is not."

If you enjoy this week’s newsletter, you might like: Melissa Etheridge’s “The Truth Is,” Carol Queen’s "Real Live Nude Girl: Chronicles of Sex-Positive Culture" or "Wild Child: Girlhoods in the Counterculture” from my Etsy shop. Paid subscribers get 10% off. Send me a message on Etsy or an email to get your discount code.