From the Archives of Minnie Bruce Pratt

Honoring the life and work of MBP, a possibility model in the form of a lusty, gender expansive femme.

When Minnie Bruce Pratt passed away in early July, I already had plans to dig into her archives at Duke. But suddenly, the timing felt more pertinent.

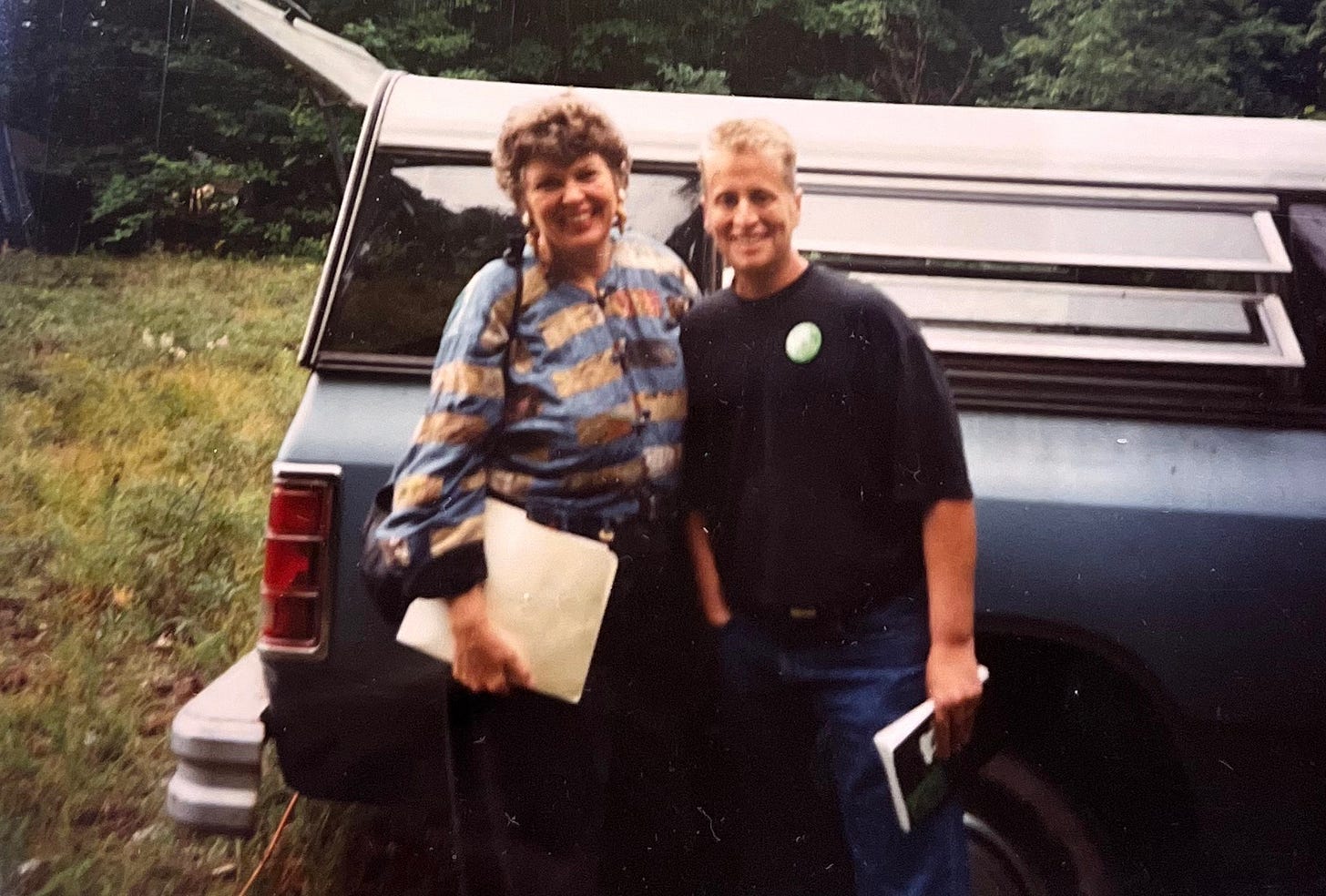

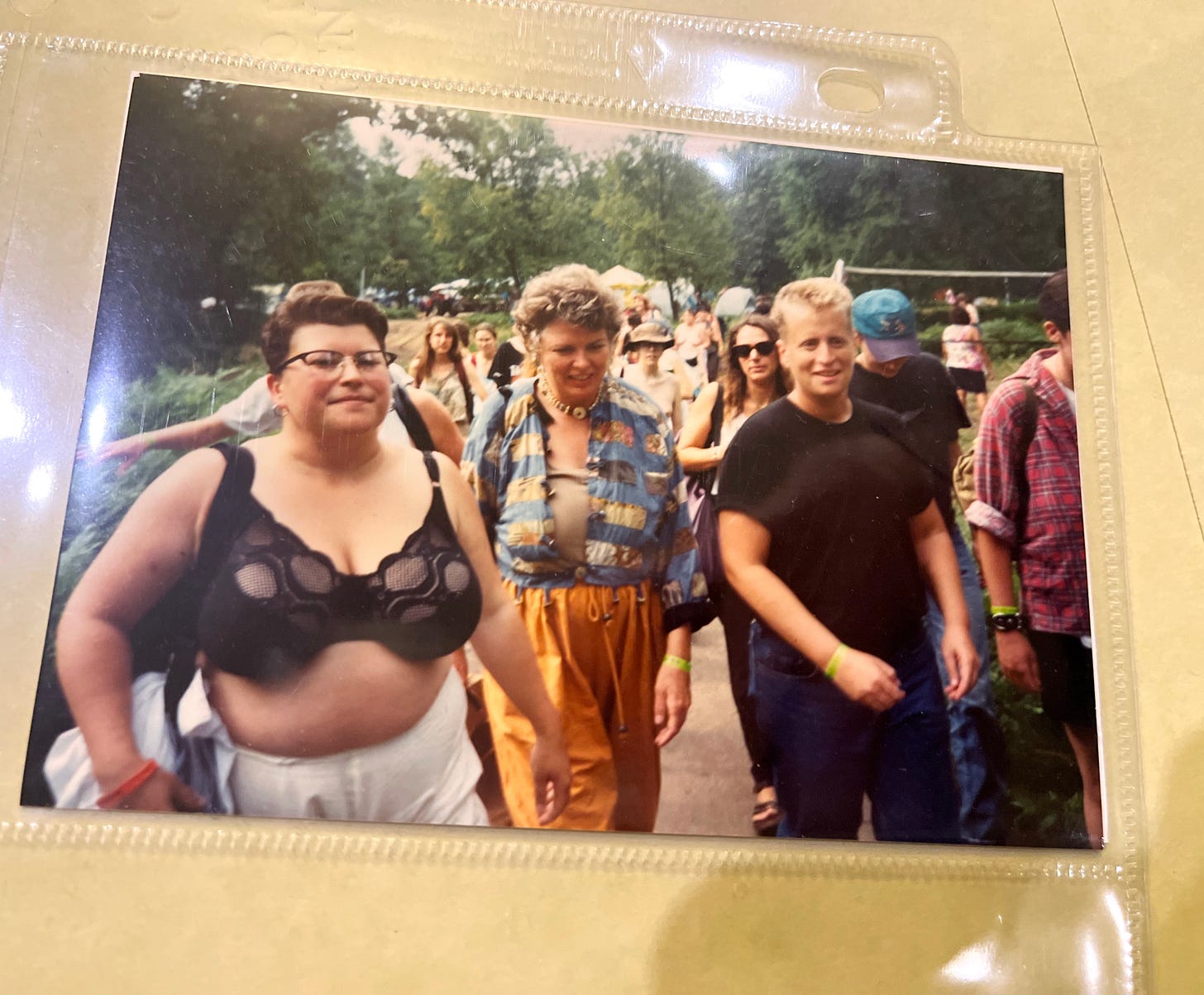

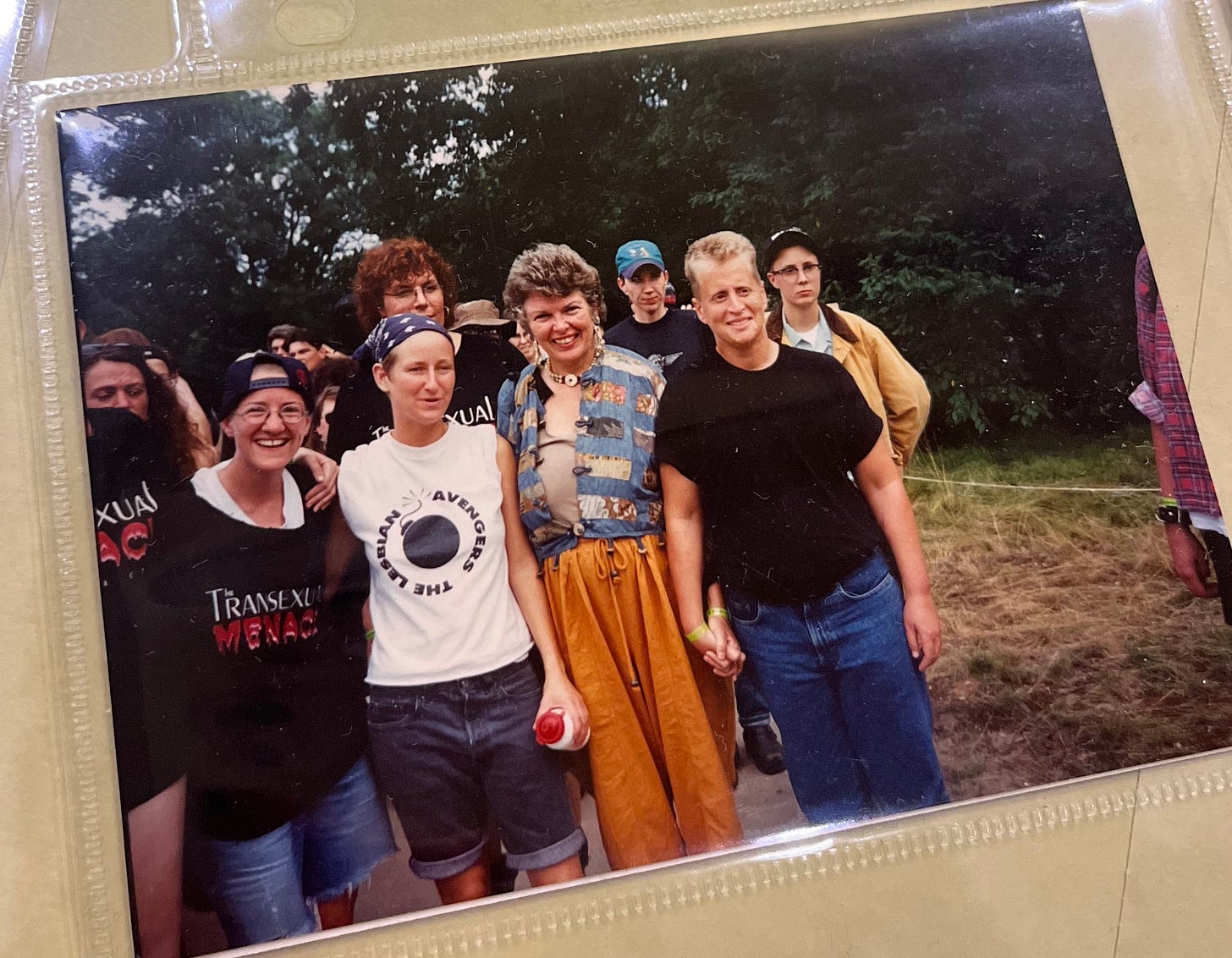

I was mostly looking for stuff related to Camp Trans, which was there, as promised — photos, email correspondence, flyers announcing Minnie Bruce and her partner, Leslie Feinberg, as guest speakers in 1994. By then, the couple had individually done both organizing and written work in the LGBTQ community as well as wider social and political movements. Combined, they hoped to lend their voices to the growing trans-affirming movement happening around the reticent Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, marching onto The Land that summer, flanked by Lesbian Avengers and leatherwomen who felt their politics were not being reflected by organizers who had asked Nancy Jean Burkholder, a trans woman, to leave the grounds in 1991. Despite their efforts as well as those of Camp Trans and its vocal supporters, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival organizers never changed their policy and, after several boycotts and financial setbacks, officially ended in 2015.

Growing up just two hours away from The Land, I had no idea of its existence as an annual lesbian pilgrimage. Learning of its proximity had been shameful — how could I not know I was a dyke when the country’s largest gatherings of dykes was happening less than 120 miles from where I’d been born?

I’d even been to Hart, Michigan, near where the land is located. Family friends had a farm there, and I’ve never forgotten my first time on a horse, there, its careless gallop taking me straight into a tree branch. It was just thin enough to scratch me across the neck, not deep enough to physically scar. Still, I was unwilling to ride a horse again for years.

I only realized my own latent lesbian feminism when I moved to Chicago for college. My gender studies and journalism classes were converging in ways I didn’t anticipate, forming a new curious consciousness when I was assigned to write a critical response to a 2003 essay by Michelle Tea as published in The Believer: “Transmission from Camp Trans.” That was when I was first confronted with the history that had been buried in my own backyard, and I’d had to leave to learn about it. Adding to the feeling of having missed out was that, despite the festival still having been in existence in that early Y2k Era, it was absolutely not chill to attend. I had invites — eventually press tickets offered, friends who continued to go and claim that the intergenerational conversations were being had on the inside, that, much like the anti-racist harm reduction, the work was being done, that it was ours to do.

Michelle’s piece revolved around a different Camp Trans than the one Leslie and Minnie Bruce visited nine years prior, but made clear the vision remained the same: Ensuring Michigan and other subsequent women’s-centric spaces were accessible and safe for trans women as well as other gender-non-conforming and non-binary individuals. (That Camp Trans became somewhat of a cruising spot for femme dykes checking for trans men before crossing back over to The Land versus a site of trans women’s liberation is an interesting marker of time in the ways lesbian/queer sexuality and politic has been worked out on/through trans bodies.)

I don’t get back to Michigan more than once a year, but could not ignore the binding tie I felt to such a historic gathering that had hosted some of the greatest feminist and lesbian minds, musicians, and culture creators from the 1970s into the ‘80s and even ‘90s, as attendees tried to reconcile their trans politics in real-time. Learning about Stone Butch Blues, Minnie Bruce and Mich Fest at the same formulaic time in my lesbian feminist development was something of a blessing — a way for me to work out my feelings from every angle as someone new to the grappling of such loaded theories that were affecting real lived experiences. It was Minnie Bruce’s writing — particularly her 1995 collection of essays, Rebellion and 1995’s S/he — that gave me a whole perspective on womanhood, belonging, and true radical feminism. Through her work, Minnie Bruce never sought to exclude or shame. She wanted liberation and freedom, from racism, anti-Semitism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia. She wrote toward it and lived not a prefigurative fantasy of a genderless life, but a steadfast and grounded declaration of defiant pleasure.

I mentioned in my last newsletter that I’d attended Fern Fest on The Land, a new trans-inclusive festival in its infancy. I was able to go only after speaking with the organizer, Abra, a wonderful woman my age from Austin, Texas who plays music, books other artists, and wanted to bring evolution to what she saw as an energetically charged environment stuck in its own muck. Despite there being trans women on the bill, I was still nervous about how it would feel to be somewhere so contentious and laden with bitter history. I worried I’d be surrounding myself with some begrudgingly in attendance with hopes to stake some kind of claim to the good ol’ days; that I was tricking myself into the same kind of utopic promise some of my foremothers insisted be free of anything outside of themselves. Like Minnie Bruce, I felt an initial unease in a place previously gatekept based on “a biological test,” even if both she and I could easily pass: “If this gathering of women in the dusty fields beyond the gate is a community based on biological purity, then it offers me, a “real woman,” no real safety.”

In the ‘70s while still married to her husband and raising two young boys, Minnie Bruce joined a feminist group who, as part of the Women in Print movement, published a newsletter, Feminary, named after the blank books that the women warriors used in Monique Wittig’s Les Guerilleres. In a piece published by The Poetry Foundation, Minnie Bruce credited the Durham-based collective with “organizing against an entrenched anti-woman, anti-lesbian, anti-sexual current that raged, deeply embedded, in all economic and social structures in the United States.” It was this space that led to Minnie Bruce’s getting published. In an oral history, Minnie Bruce recorded the same year I read “Transmissions from Camp Trans,” Minnie Bruce said, “The conversations that we were having about what did it mean to be a lesbian and a Southerner and antiracist, and all that — that’s really why I started writing essays.”

It was through Feminary she began to understand her queer desire and the ways oppression had sought to silence her in enduring ways. Growing up in the South, she had no means to confront the racism of her surroundings — including her family’s slave-owning lineage. Her attraction to other girls — usually tomboys and other gender skirters — was festering, dormant until women’s liberation provided a chance to consider these feelings not only valid, but actionable, as were her beliefs in the ways the world could change. After coming out as a lesbian and losing custody of her children, she put the painfully cruel details into the crucial memoir of motherhood, Crime Against Nature.

Her work took guts, and I can confirm that having been deep inside her archives, she never profited greatly, at least not in monetary ways. She and Leslie were frequently traveling on the cheap, staying in cheap motels and strangers’ bedrooms in order to make appearances at now-defunct feminist and queer bookstores, at long-gone LGBTQ writing conferences, and, for one historic year, Camp Trans. On the program for Camp Trans in 1994, MBP is listed as hosting a Saturday morning conversation: “Gender Bending and Me: "Get mushy with Minnie Bruce Pratt as we serve oatmeal and she presents a lesbian feminist journey through gender reading from her new book S/he.”

My first day on The Land, I immediately joined the Femme Parade in my lesbian flag dress. A small but mighty group, we traipsed up and down the paths of Lois Lane and Womb Way, every tree a marker of time, holding a heavy history in her roots, extending out from her branches. I thought of Minnie Bruce Pratt, marching next to Leslie, the leather women, the Lesbian Avengers. I carried her with me.

In a piece from S/he called “Border,” Minnie Bruce writes about her experience marching onto the land with Camp Trans — the gender and genital policing at the gates of Mich Fest, the eeriness she experienced “looking and sounding” like other women there, a similar mirroring sentiment she expresses in an earlier piece, “Sister” wherein she hopes no one conflates her with another lesbian attends a conference with, lest her colleague’s internalized misogyny and homophobia suggest we’re all one and the same (“I might argue with her all the way, but I’m arguing with myself: How to be a woman?”)

“I stand on the sandy road that runs between the two encampments, at the boundary of womanhood,” Minnie Bruce writes in “Border.” “I don’t want woman to be a fortress that has to be defined. I want it to be a life we constantly braid together from the threads of our existence, a rope we make, a flexible weapon stronger than steel, that we use to pull down walls that imprison us at the borders.”

I was only in direct contact with Minnie Bruce once in 2018, while working on a story about a potential film adaptation of Stone Butch Blues. Having outlived Leslie (who died in 2014), Minnie Bruce held to her promise that she would never comment publicly on her late partner’s behalf. She directed me to Leslie’s own words, on Leslie’s website, Leslie’s want for SBB to be made freely available but never commodified. When I spoke to Feinberg’s friend, lesbian historian/editor Julie Enszer, for the story, she said she believed Leslie’s hope was to serve as inspiration for the future of queer, trans and otherwise expansive work that was born out of books like Stone Butch Blues — a jumping off point for further writing that offers alternatives to the rigidity of “womanhood.”

Like many others, Stone Butch Blues was incredibly important to me as a baby dyke femme finding her way through a desire for masculine of center women and other gender outlaws. Minnie Bruce Pratt’s S/he was from another perspective — a femme’s POV, detailed in vignettes grappling with gender, sexuality and judgment; “womanhood,” “manhood,” a “both/and” existence that allowed for growth, truth and complexity. It’s in Minnie Bruce’s stories that I find space for myself, in my questions, my missteps, my ownership of self and the space I take, create or participate in.

Without Minnie Bruce, I would never have gone to The Land, and The Land would not be a place of possibility now, where it once felt impossible, at least to me.

When Minnie Bruce’s sons offered an opportunity to send her a message one month before she passed, I hurriedly dashed off a note to her on the provided Google form, thanking her for all she’d contributed through her work and example. I wished I had something more tangible to offer her, seeing how she’d given me so much and I’d never had the pleasure to meet her and tell her just how much she’d done in her time on this earth; that her time spent, though too often underpaid or seen as secondary to her partner’s notoriety, was life-changing. The best I can do is to help keep her work alive through life, work, and practice. I choose to see her passing as a reminder of the impact one person can have, and the opportunity to see through her lens in her archives as an invaluable gift she left for us all.

"Now I know that in order to keep hoping, and living, and writing, I need work from other women that is rooted in the messy complexity of our daily lives, work in which we upset the predictable ending. I need all the voices of the women who have been destined for despisal, anonymity, or death, but who, defiant, have survived and lived to tell their triumph." — Minnie Bruce Pratt, 1991