Experiencing the Ecstasy of 'Female Perversions'

The queer, feminist Tilda Swinton film that I can't stop thinking about.

This morning, I woke up to a voice note from a friend telling me she was still thinking about the movie we’d seen over the weekend. I smiled when I heard her say so because I hadn’t been able to stop thinking about it either.

We’d been virgins going into the new restoration of Female Perversions — aka Tilda Swinton’s 1996 Hollywood debut. I prefer to go in blind, so I knew very little other than Tilda’s character was #bisexual, and the film was as provocative as its title suggested. How so depends on the audience’s ability to stomach what has proven too challenging for some: During the Q&A after the screening, Susan Streitfield shared that at the original Sundance premiere, only five people stayed for the entire showing.

A painter-turned-high-powered agent for stars like Juliette Binoche and Daniel Day-Lewis, Streitfeld adapted Female Perversions from the feminist psychoanalytic theory described in Louise J. Kaplan’s 1991 book of the same name. Characters like Tilda Swinton’s Eve and Amy Madigan’s Maddie play out the “perversions” of gender roles. Eve is a ball-busting, image-obsessed attorney in Los Angeles whose reputation for appealing to the boys’ club has given her a leg up for the judgeship she is desperate to achieve ("I want to wear that long, black robe with nothing on underneath,” she tells Renee.) Her sister, Maddie, is a kleptomaniac living in a rural California town where she rents a room in a house with a single mother and her rebellious androgyne pubescent daughter, Ed, while preparing to defend a dissertation detailing a matriarchal Mexican village (“They're all fat,” Emma says. “That's what happens in a matriarchy.") Though generally estranged, the sisters reconnect when Maddie is arrested for shoplifting, just as Eve is preparing for a job interview with the governor. One of Eve’s perversions, Streitfeld says, is homeovestism — an erotic reaction to wearing clothing expected of one’s sex.

“A perversion is a psychological strategy,” Kaplan writes. “It differs from other mental strategies in that it demands a performance.” And women are always performing unless, of course, they decide not to.

Streitfeld called Kaplan’s book “very freeing … because it ultimately talks about behavior in terms of attaching it to history, society and family. So it's not as if I'm the only person with this behavior in the world, and I am fucked up around it."

So, where do the female perversions come in, you ask? They’re quite literally embedded within. A section from Kaplan’s book appears in the prologue:

“For a woman to explore and express the fullness of her sexuality, her emotional and intellectual capacities would entail who knows what risks and who knows what truly revolutionary alteration of the social conditions that demean and constrain her. Or she may go trying to fit herself into the order of the world and thereby consign herself forever to the bondage of some stereotype of normal femininity – a perversion, if you will.”

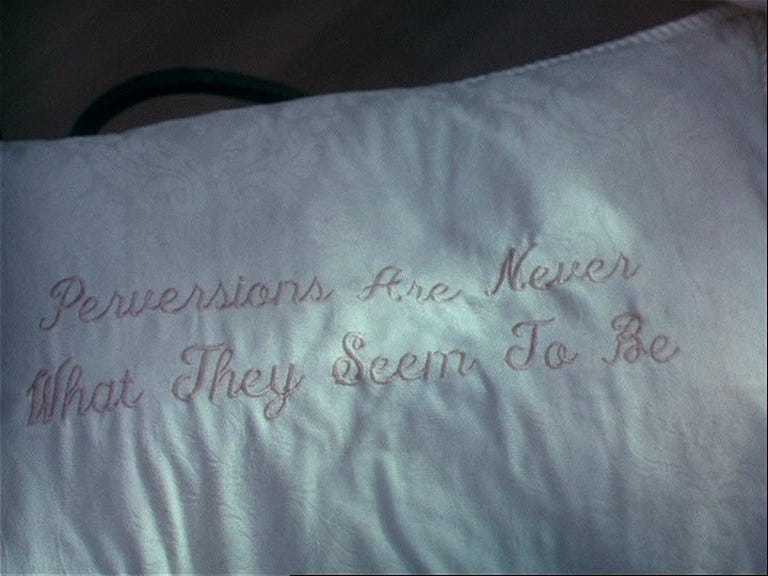

Her ideas also appear throughout, embroidered on pillows (“Perversions are rarely what they seem”) and graffiti (“Perverse scenarios are about desperate need”), surrounding Eve as she engenders masculinity while masquerading femininity in an unchecked lust for power — until now. Haunted by demons in tight-rope walking dream sequences, she begins to experience the horrors of self-inflicted bondage in waking life when voices tell her she’s imperfectly too wide in the hips or she imagines a stranger calling her a fraud who will soon be found out. It takes most of the film for Eve to see that the parameters of perfection have been predetermined for her (through society and her family) and that she must answer the call from inside the house.

If this doesn’t sound erotic to you (though Kaplan and Streitfeld might argue it should), then I’ll tantalize you with the more blatant sexual nature of the film, which is Eve’s relationships with John, a wealthy (male) seismologist and Renee, an emotionally adept blonde psychiatrist (Karen Sillas). Eve is dominant in both arenas, though neither of her partners always appreciates that approach. With John, Eve tops from the bottom, demanding his availability when she requires him and asks that he dry shave her with a disposable razor despite the pain he reminds her of the regrowth. With Renee, Eve is the seductive aggressor, which Renee enjoys but is cautious of. She playfully calls Eve out for being a "deeply compulsive, neurotic, codependent woman, who probably loves too much, or too little." (“I'm so glad someone understands me!" Eve says from where she lays on the patient’s couch in Renee’s office.) Later, a sexual rendezvous goes South when Eve is overly aggressive, lost inside herself, while Renee cries out for her to stop. “Where are you?” she asks, but Eve can’t answer yet.

Maybe you can see why my friend and I are still considering this film.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LIT FEMME to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.