"Dyke Strippers" and Other Works of Art and Allyship

Roz Warren's '90s feminist humor collections are queer time capsules in cartoon form.

Last year, I was conducting some research at the June Mazer Lesbian Archives in West Hollywood when I spotted the spine of a book that I’d never seen before but had to know more about: Dyke Strippers.

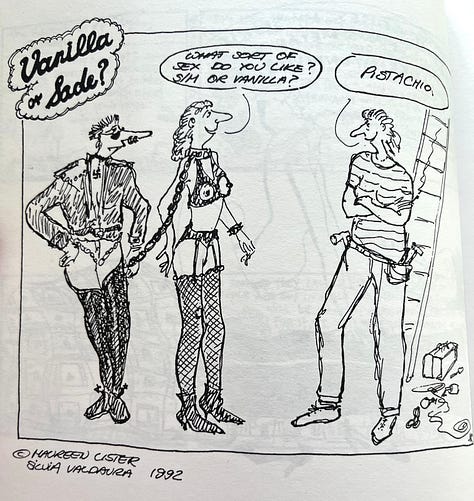

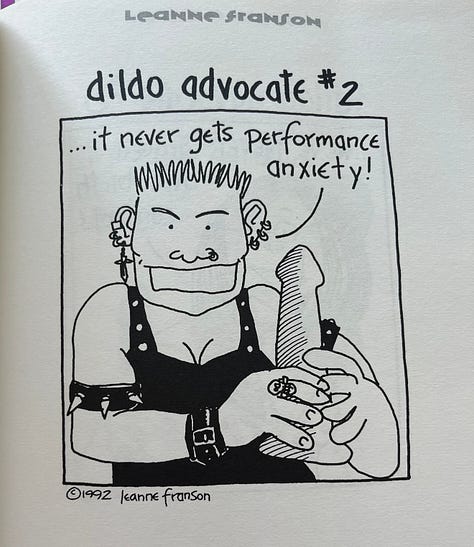

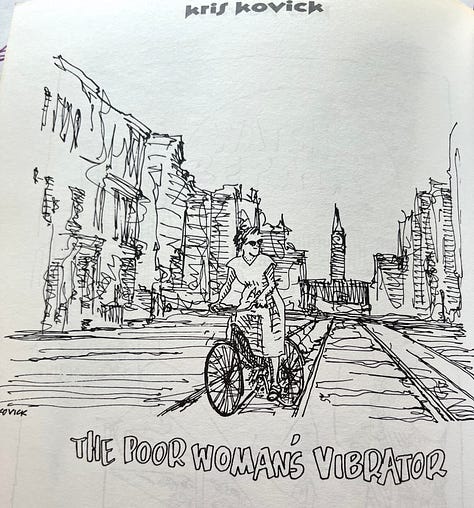

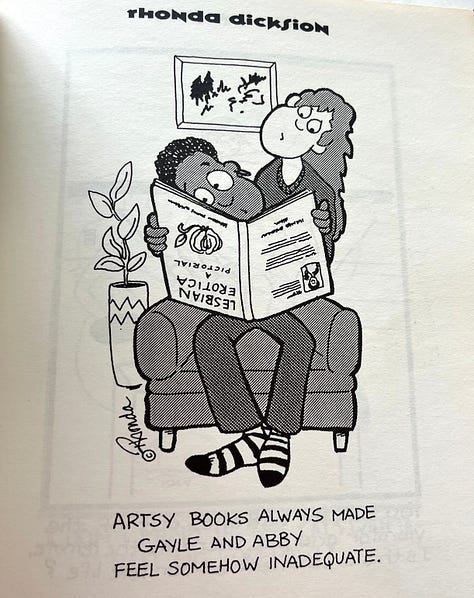

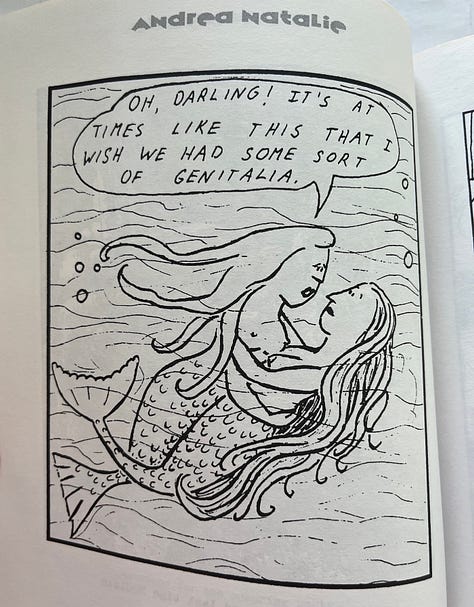

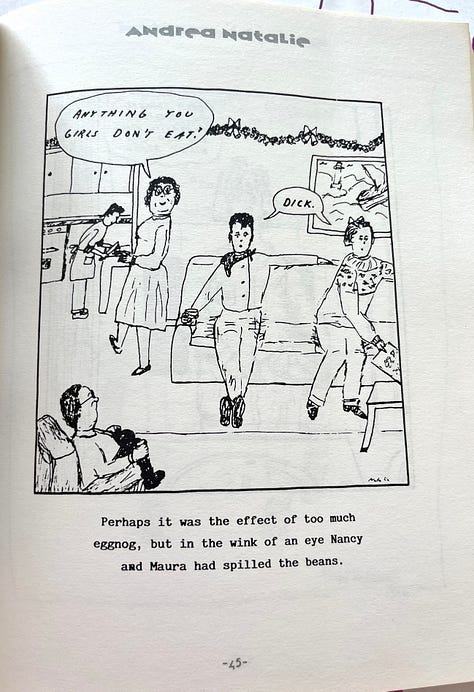

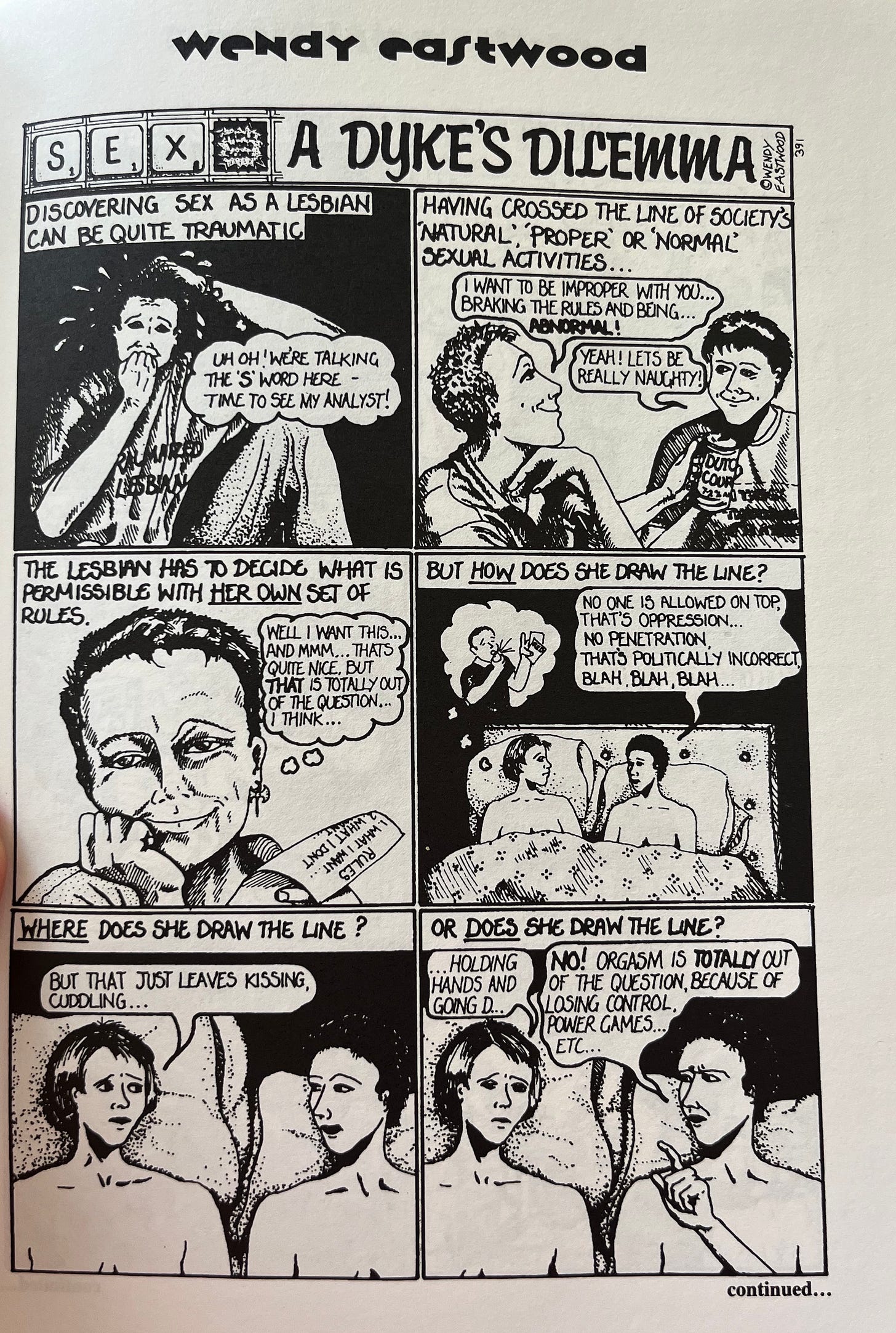

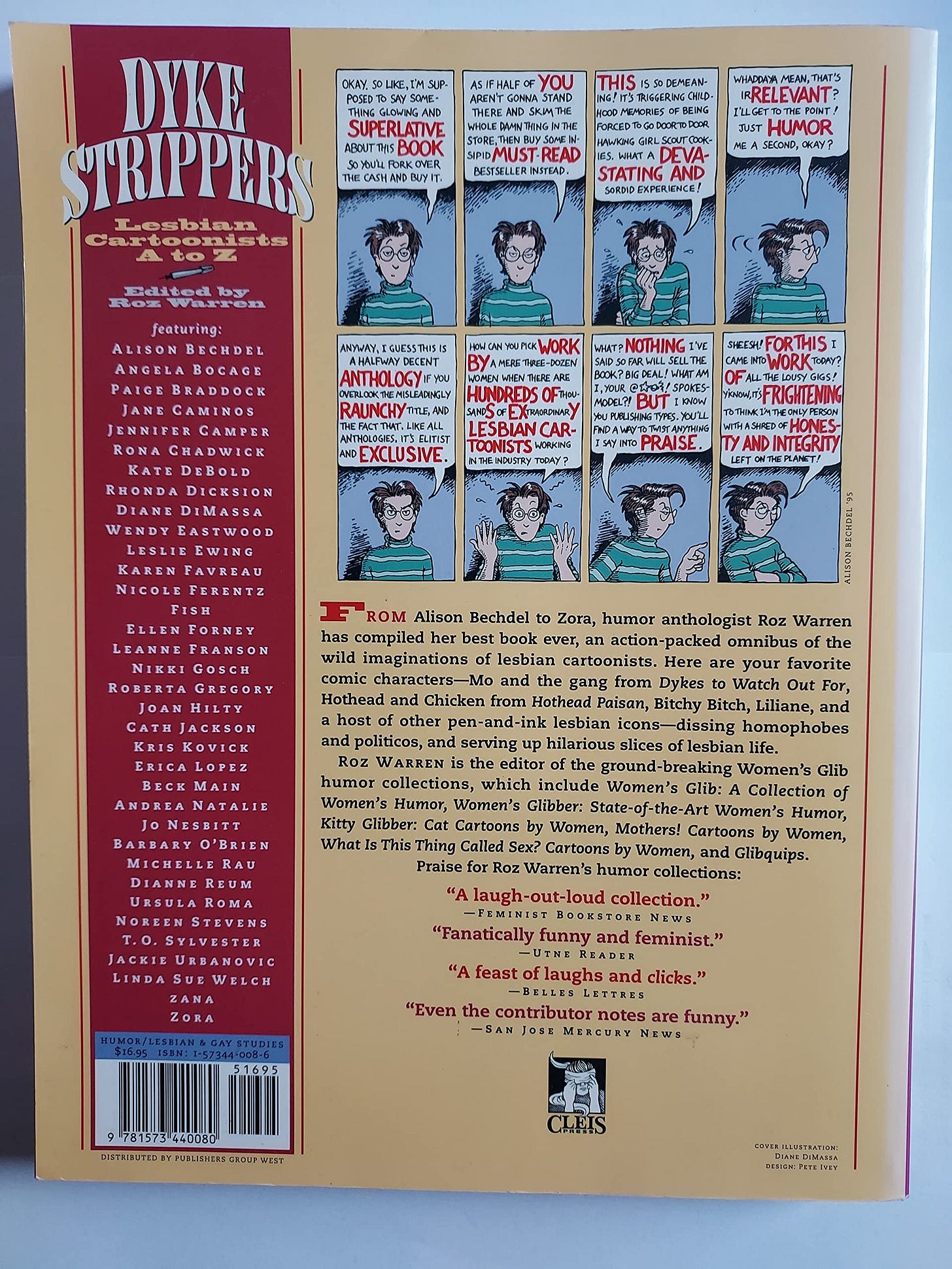

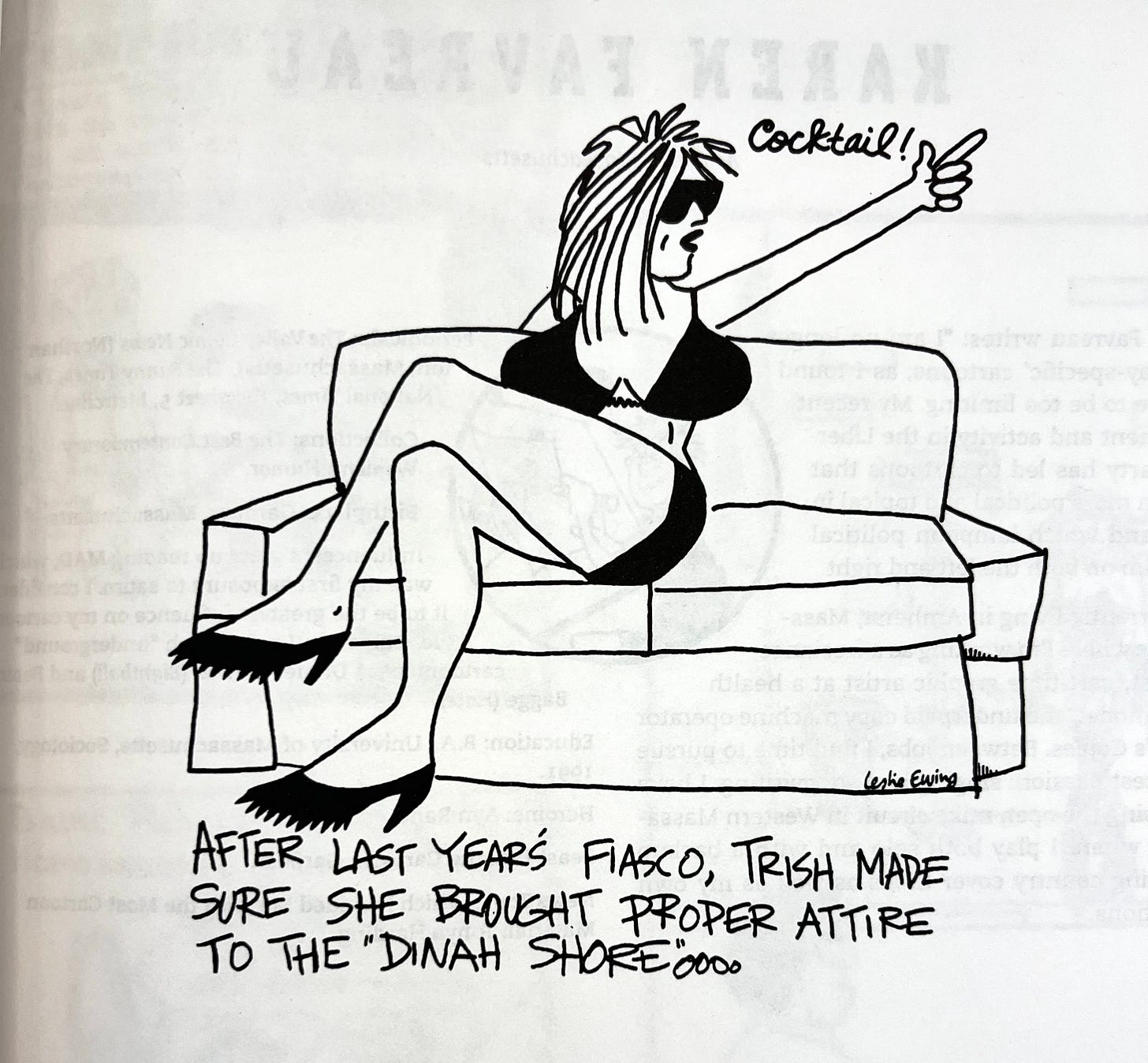

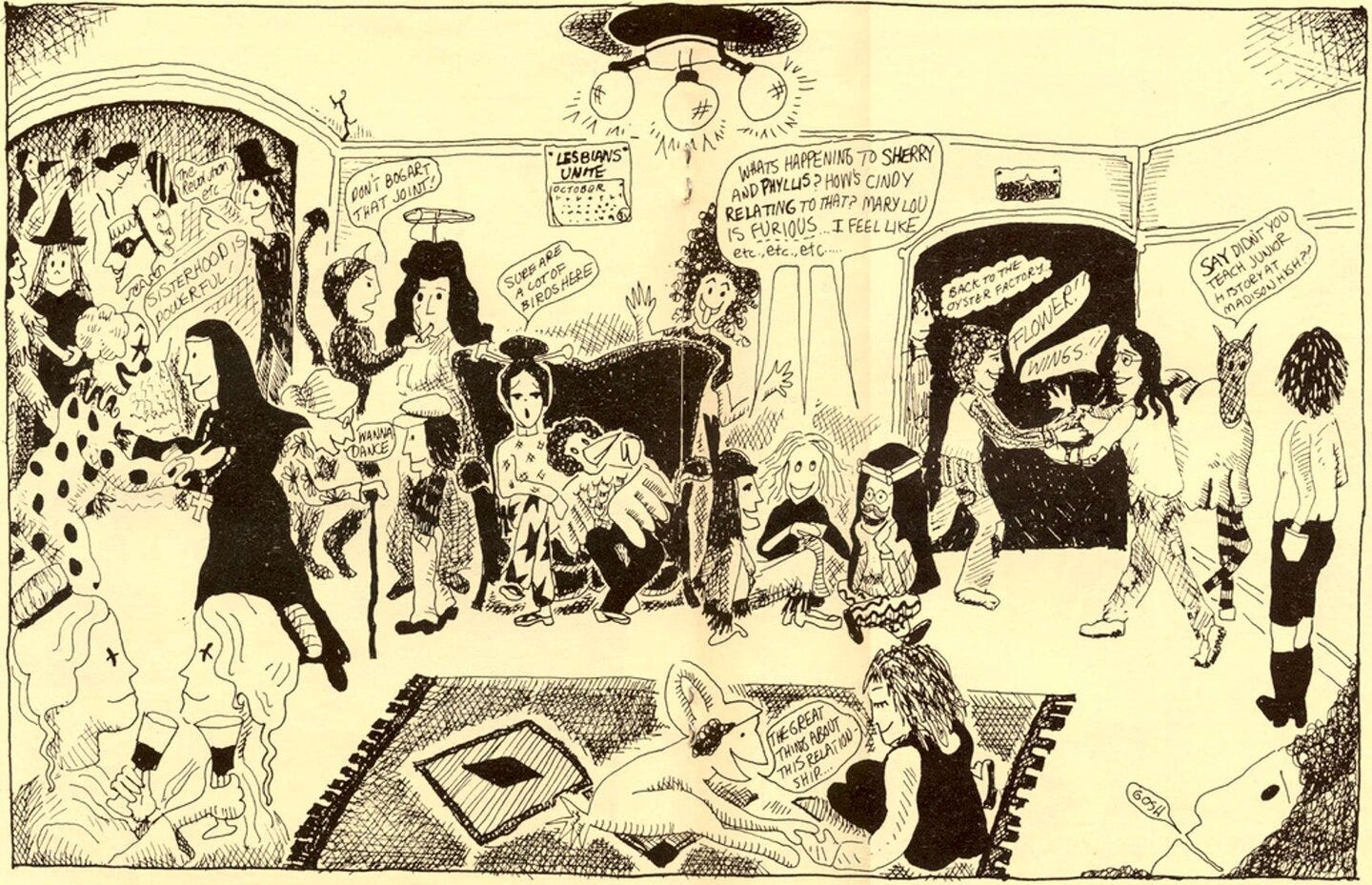

When I pulled Dyke Strippers from the stack, I was thrilled — no, ENCHANTED — by Diane diMassa’s work on the cover: two bra-less grotesque punks with body hair and shitkickers disrobing on stage, more of a taunt than a titillation tactic. It hinted at the playfulness of the book’s insides, where I found familiar names like DiMassa, Alison Bechdel and Ellen Forney next to others I was newly discovering, like Andrea Natalie, Kris Kovick, Jennifer Camper, Joan Hilty, Leslie Ewing, and Nicole Ferentz.

Editor Roz Warren wrote in the introduction that Dyke Strippers was her 10th women’s humor collection and that, in the process of collecting work from women humorists, she’d become quite a fan of queer women cartoonists. She bemoaned their erasure in mainstream venues, largely due to their being ghettoized and sequestered to regional LGBT papers where they found but were limited to local audiences.

“Still, this book is the first opportunity most readers will have to enjoy the work of so many talented lesbian and bi cartoonists who are currently cartooning. There's nothing like being able to phone a cartoonist whose work you love, and have a long, interesting conversation about her art and her life. I hope that reading this book will be the next best thing.” — Roz Warren, February 1995

That day at the archives, I soaked up as much as I could of Dyke Strippers, which, like all of Warren’s books, is now sadly out of print. It wasn’t until recently I found a copy of another one of Warren’s works out in the world that I remembered the historical treasure it was, and promptly purchased What Is This Thing Called Sex?: Cartoons By Women, which included several of the same queer artists in the inclusive and sex-positive book published two years before Dyke Strippers.

Looking into Warren, I quickly found out that she was straight (but not narrow! OK, ally) and I had to know more about the relationships she’d built with queer feminist artists in the ‘90s. She was gracious enough to be interviewed over the phone, where she told me the initial inspiration for collecting women’s humor was the pervasive and maddening myth that women weren’t funny.

“There are all these humor anthologies that contained nothing but work by men — maybe one token woman,” Warren said. “There'd be one piece from Nora Ephron about how her boobs were too small. People would say, ‘How come there are no women in there?’ And the male editor would say, ‘Well, there aren't any women writing humor and if they are, they’re not as funny.’”

But Warren knew that wasn’t true — she’d been reading hilarious work by women writers in feminist and LGBT newspapers for years, collecting comic panels and columns in drawers.

“All of a sudden, you have a whole book full of funny women,” she said.

A third of what ended up in Warren’s first collection, Women’s Glib: A Collection of Women's Humor (1991), came from her own personal stash. The rest came via calls for submissions in feminist periodicals and shaking the lesbian phone tree.

“The great thing that I really want to emphasize about women writers and women's humorists is it's really a sisterhood,” Warren said. “They were really helping each other out. There were so many women who basically saw that this was an opportunity and wanted to share this opportunity.” There was little competition or envy, as Warren’s work to publish as many women as possible in promised future collections proved eschewed concerns about scarcity.

When Women’s Glib sold 20,000 copies, Warren saw that feminist humor could be successful, by small press standards. And unlike the few other women’s humor collections that had been produced over the years, Warren’s situated lesbians and bisexual women alongside their heterosexual counterparts in ways that were respectful and validating.

“Before that, they might as well have been called ‘Straight Women's Humor Collection,’” Warren joked.

A straight married mother in the early ‘90s, Warren said she became “an expert in lesbian cartooning” while championing the work of queer women who were frequently without opportunity or proper compensation.

“I made it my business that I could publish and pay for work and, and spread the word about them so that everybody knew I was on their team,” Warren said of lesbian artists. For Dyke Strippers specifically, she sought consent.

“I asked Alison Bechdel, ‘OK, even though I'm straight, is it kosher for me to put this book together?’ And if she said to me, ‘No, yeah, you may not — that's cultural appropriation’ or whatever, I would've backed off because I figured she's the person whose morality in this and judgment I trust. And she said, ‘If there were a lesbian who was doing this book, I would say to you that you ought to help that person, and let that person do it.’ But there wasn't. So she said, ‘Given that there's not a lesbian, you go right ahead because I trust that you'll do a good job.’”

With The Bechdel Blessing, Warren sought out the now-defunct lesbian-centric Cleis Press for Dyke Strippers. She was pleased with the quality of the book and paper stock and said she felt supported by a well-connected network of women’s bookstores, gay bookstores, women’s presses and newspapers, many of whom invited her in for slideshows and signings or published generous reviews.

”I'd sort of carved out a little niche,” Warren said. “And when I would show up at these women's bookstores and there'd be these cartoons that were very, very pro-women and very, very pro-lesbian, and you'd get this audience of people that were just so thrilled and excited to be there and just laughing up a storm, it was just a joy.”

Warren calls Dyke Strippers “a great big Valentine for the people who were in the book,” saying lesbian culture has always appealed to her in that it “does not center men.” Frequently assumed gay because of her queer inclusion and feminist POV, Warren aligns herself politically with lesbians if not sexually.

“I loved a lot of where lesbians were coming from,” she said. “A value of lesbians at that time was an emphasis on inclusion, which may still be the case very much. They were always pushing me. People would review my book and say, ‘This is terrific. It's funny, but there should be more people of color. There should be more people with disabilities. We want more inclusion.’ And the other value that I thought was really cool was consensus — and these are two things that I still think are really cool and the world needs more of.”

Warren’s other books include collections of women’s cartoons about cats, divorce, and library humor, each individual selection based on the criteria that she finds its content funny and inoffensive (no self-deprecation or body shaming allowed). Despite the publishing establishment’s sad ignorance of funny women, Warren continues to have no trouble finding feminist artists whose work should have the chance to be enjoyed widely — she still gets submissions in the mail.

”My feeling as a feminist is that all women should be empowered,” Warren said. “I wanted to mainstream all of the voices that I was publishing because I felt they all deserved to be heard, and they all deserved to be able to make a living doing what they did because they were good at it.”

Several of the artists Warren published over the last 30 years have expressed their gratitude for her giving them the motivation to continue — “especially cartoonists,” she said, some of whom were able to get their own deals after being published in books like Dyke Strippers.

”If you look at Alison Bechdel, this is someone who was helping define the culture she was writing about, and there were people who wanted more,” Warren said. “They were like, ‘OK, I'm addicted to Dykes to Watch Out For, what else can I start reading?’ I helped people discover Hothead Paison and they were just enchanted.”

Sadly, Dyke Strippers and Warren’s other books are available from select libraries and used resalers online, with no plans to reprint any in the future.

“They're time capsules,” she said. “No one's interested in a collection of women's humor from 1995.”

Maybe so, but I couldn’t have been happier when she offered to send me my very own copy.

For more history and context on the lineage of lesbian and queer comics, I recommend Vivian Kleiman’s 2021 documentary No Straight Lines, available to stream via PBS Independent Lens featuring pioneers like Mary Wings, Roberta Gregory, and Trina Robbins. In the documentary, Wings talks about finding Robbins’ Wimmin Comix at a long-gone Portland women’s bookstore and being inspired to create her own work like Come Out Comix and Dyke Shorts.

"I wanted women to have some things that mirrored their experience that felt good,” Wings says in the film, “because most of us just settle down into lives that are pretty repetitive, and I wanted my sisters to go on an insane adventure while they're sitting in their armchairs and have to go to work the next day."

Click the button below and use the promo code STONEWALL for 10% off any books in the Lit Femme Etsy Shop between now and June 27. Happy Pride!

Thanks so much for this great piece! You're a terrific writer. I had a lot of fun talking with you and remembering what everything used to be like. And I've got your own personal copies of Dyke Strippers, Weenietoons and GlibQuips sitting by the door waiting for me to get to the post office and mail them to you.